Publications

A Special Publication in cooperation between INSS and the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage Commemoration Center (IICC), July 24, 2024

Introduction

On January 30, 2020, Na’ama Issaschar, a 26-year old Israeli-American backpacker, landed in Israel. She was accompanied by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who traveled to Moscow especially to bring her home. The only words she uttered were: “Thank you... I am still shocked.”[2] Her shock was understandable. She was arrested in April 2019 at a Moscow airport for allegedly possessing a minuscule quantity of drugs, for which she was sentenced to 7.5 years in jail. She was released after lengthy high-level negotiations between Prime Minister Netanyahu and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The enigmatic nature of this affair and its rapid transformation from a seemingly mundane case of injustice to a high-level political affair raises multiple questions. Was this an ordinary case where a relatable human story attracts attention from the media? Or was this a case of a Russian information war where various Russian actors worked in cooperation and coordination across domains to influence Israeli media and public discourses and to affect political decision-making?

By analyzing primary materials, mainly from leading Israeli Hebrew-language media outlets (Ynet and Mako websites), which aim to appeal to the general Israeli public, and the website of the Russian state-backed news outlet Russia Today (RT), this paper sheds new light on the story of Issaschar and the related story Aleksei Burkov—a Russian hacker arrested in Israel whom Moscow demanded to be traded for Issaschar.[3] It reveals the case as a Russian informational-psychological influence operation in Israel, in which RT played a key role. RT is a Russian news channel aimed at foreign audiences, owned, and financed by the Russian government. It is widely considered an important component of the Russian state toolbox of information war, while its practices are inconsistent with journalistic ethics.[4]

This operation took place long before the Israeli authorities recognized the threat of Russian malign influence operations in Israeli politics.[5] The article demonstrates that RT acted in coordination with other Russian government bodies, and its coverage of the case helped the Russian state exert pressure and extract diplomatic gains from Israel. Consequently, it shows the holistic approach of Russian state actors to information and media space, where media coverage (including the use of manipulative narratives) works to advance the Kremlin’s interests in the international arena.

This is the first attempt to examine the Issaschar affair as an informational-psychological influence campaign within the Russian framework of information war. Prior to this research, Issaschar’s case was never investigated in Israel or elsewhere as an information campaign and was reported in Israel as a case of political extortion where Issaschar was described as “a tool in a game” or a “bargaining chip.”[6]

The limited scope of this article meant that we could not encompass the complex and, at times, contradictory roles of the various actors involved in this affair. Most of the Russian and Israeli activities on this matter are not available in the public domain, difficult to investigate, and draw robust conclusions. In this article, we refrained from discussing RT’s probable coordination with the various Russian security agencies, the legal system, the courts, and the political leadership implied by the timeline and the dynamics of this affair. We also decided not to discuss the involvement of religious organizations such as Jewish Chabad and the Russian Orthodox Church, which played a role. Nevertheless, focusing on RT’s role suffices to demonstrate that the Issaschar affair is an example of Russia’s information war in Israel.

The article is divided into four parts. First, we present a review of the theoretical framework of the “information war” and the methodology employed in this article. Second, an overview of the timeline of the detentions of Issaschar and Burkov, which is the result of an open-source investigation by the authors, is laid out. This recount of events provides background to the third part, where we offer empirical evidence that Russian state actors, including RT, participated in a coordinated information operation. Last, the article discusses the impact of the operation on Israeli narratives.

Theoretical Frameworks and Methodology

The academic debate on Russia’s information and influence efforts has received considerable attention.[7] These studies point to a growing metamorphosis between information, international relations, and conflicts in Russian strategic thinking.[8] They focus on explaining Russian information operations’ strategies, doctrines, techniques, and cultural traits. Such Russian activities have been termed in various ways, including “hybrid war,”[9] “active measures,”[10] “cross-domain coercion,”[11] and “information war.”[12]

This article will take a slightly different approach, relying on authentic Russian terms to provide a theoretical framework that explains the country’s activities in the information space and the role played by RT.[13] In Russia, the debate on influence activities in the information space is permeated with war-like metaphors. The most popular term to describe such activities is informatsionnaya voyna or “information war,” within which operations of informatsionno-psikhologicheskoye vozdeystviye or “informational-psychological influence” occur. In the Russian context, these terms describe a combination of military and non-military methods aimed at influencing the information-psychological landscape of a targeted audience.[14] The current article will consider Issaschar’s case within this authentic Russian terminological conceptualization.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no official public Russian doctrine on “information war.” Yet, we found that various Russian institutions and agencies conceptualized the securitization of the information domain. Russian writing on the subject in the past 15 years has described the information war as a cross-domain confrontation where political, economic, diplomatic, and media spheres are deeply intertwined, and civilian and security state actors are expected to work together.

The Unusual Story of Na’ama Issaschar

On April 9, 2019, Issaschar was on her way back from India to Israel via Moscow when she was arrested at the airport.[15] She was told that nine grams of Indian Hashish were found in her checked-in luggage, and she was being charged with drug possession, which was later aggravated to drug smuggling.[16] At this point, from diplomatic and legal perspectives, there was nothing extraordinary about Issaschar’s case, as there have been hundreds of Israelis imprisoned abroad for drugs and other offenses, justified or not, while the Russian judicial system has been known for being particularly punitive and Kafkaesque.[17]

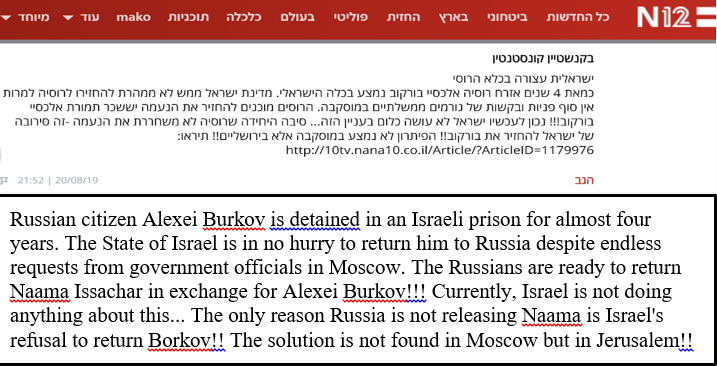

In August 2019, Issaschar’s family appealed for help from the Israeli government through the media. The Israeli media portrayed the case as the maltreatment of a young girl by the Russian authorities, but the story failed to attract much attention.[18] Yet, behind the scenes, the idea of trading Issaschar for a Russian citizen jailed in Israel was being proposed. On at least two occasions in August and September 2019, a person who called himself Konstantin Bekenshtein left public comments on Mako (see Figure 1). He claimed that “The Russians are ready to give back Issaschar for Aleksei Burkov!!!” and that “[The] girl will return home only in exchange for the release of a Russian citizen named Aleksei Burkov.” Bekenshtein obsessively contacted Issaschar’s family with similar suggestions. Israeli journalists found later that Bekenshtein was a Russian-speaking Israeli of dubious background who, in the past, had served a jail sentence for fraud at the same prison where Burkov was awaiting extradition, making it possible that they had met in prison.[19]

Aleksei Burkov is a Russian national who was arrested in Israel in December 2015 for cybercrimes committed in the United States and was awaiting extradition. In hindsight, Bekenshtein’s online comments should have raised concerns in Israel about possible political motives behind Issaschar’s imprisonment in the weeks before Netanyahu asked Putin to release her and received an official demand to exchange her for Burkov.[20] But the comments were odd and likely were not identified by the Israeli government, and were ignored by the media and Issaschar’s family. As such, Issaschar 4r53\]444eremained largely anonymous.

Figure 1. Comments Left by Bekenshtein About Issaschar in N12 (August 20, 2019)

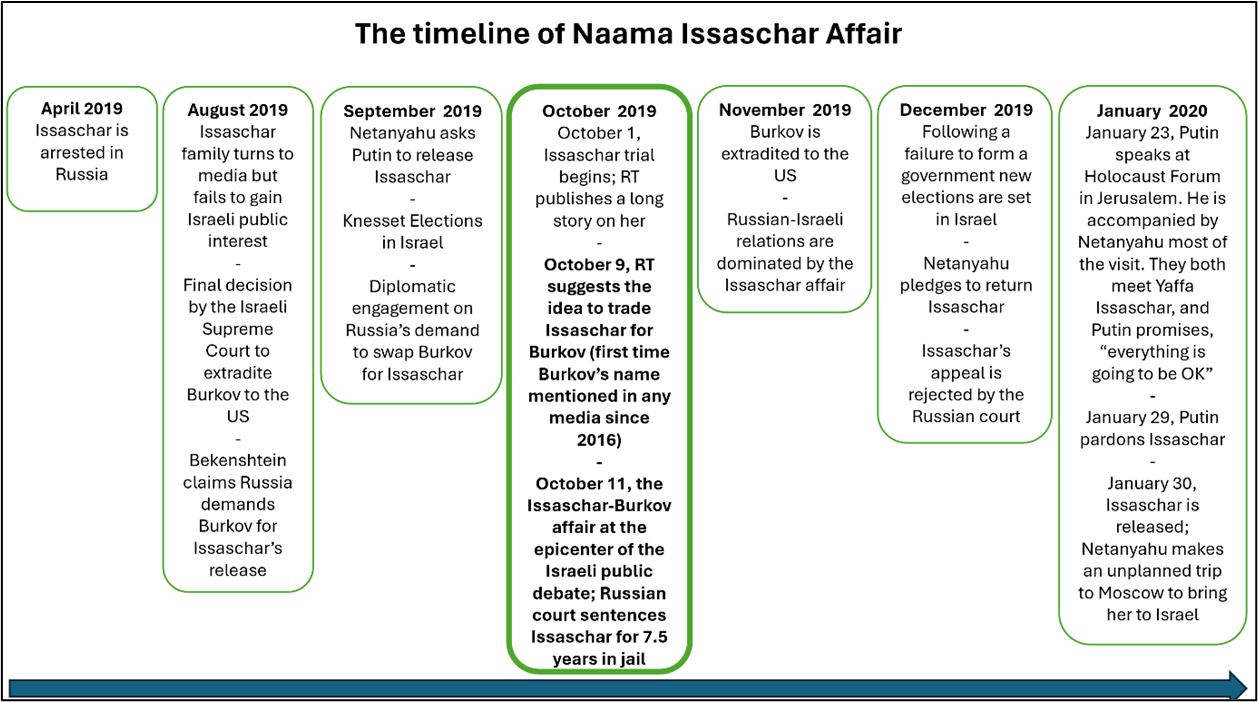

Issaschar’s case gained Israeli public attention in October 2019 (see Figure 2). On October 1, Issaschar’s trial commenced in Russia. Although it was hardly reported by the Israeli media, Daniil Lomakin, the senior editor of RT in Russian, devoted a magazine article to Issaschar on RT’s website.[21] A week later, on October 9, Lomakin, wrote another magazine story that became crucial for Issaschar’s fate. In his second story, Lomakin focused on the jailed Russian hacker Aleksei Burkov. Lomakin interviewed Konstantin Bekenshtein (who left the comments a few months earlier), introducing him as a friend of Burkov and the instigator of a possible prisoner exchange.[22]

Figure 2. The Timeline of the Na’ama Issaschar Affair

On October 11, 2019, the day of Issaschar’s sentencing, the Israeli press began intensely reporting about a possible swap between Issaschar and Burkov, quoting Lomakin’s article on RT. In the mid-day, the Prime Minister’s Office confirmed Netanyahu’s involvement in behind-the-scenes efforts to help Issaschar and implied Israel’s refusal to swap her for Burkov.[23] In the afternoon, Issaschar was sentenced to 7.5 years in prison. Israel declined to swap Issaschar for Burkov, and he was extradited to the United States in November 2019. Interestingly, the negotiation for Issaschar’s release continued for more than two months afterward.

Russia’s suggestion for a prisoner swap and Issaschar’s disproportionate punishment had an extraordinary effect on the Israeli media. It ignited unprecedented interest and an outpouring of sympathy for Issaschar. From October 11, 2019, until her release from prison in January 2020, Issaschar’s case became one of the most reported items in the Israeli media. Netanyahu and his rival Benny Gantz, who were embroiled in a domestic political deadlock and recurring elections, became publicly committed to efforts to release her, which dominated Israeli–Russian relations for months. Amid the barrage of news reports, magazine articles, and public initiatives, one senior Israeli official even asked the public to “pray for Na’ama.”[24]

While much of the intense reporting by the Israeli media on the Issaschar affair was organic, RT continued to influence the Israeli media’s agenda. For example, Lomakin, RT’s correspondent, visited Issaschar in prison and concealed his RT affiliation from her, presenting himself as a human rights activist and thus deviating from ethical journalistic standards.[25] Thereafter, Lomakin released photos and described how Issaschar was “practicing yoga and learning Russian.”[26] Significant interest in Issaschar prompted Israeli Channel 13 to interview Lomakin, where he once more was introduced as a “human rights activist” who wanted to share “optimistic messages.”[27] Our research discovered that Lomakin had become a member of Russia’s state-sanctioned Public Supervisory Commission only a day before he published his piece on a possible Issaschar-Burkov swap,[28] which allowed him to visit Issaschar in prison. He was appointed to that post as part of a government purge that replaced genuine human rights activists with regime loyalists.[29] Lomakin was evidently trying to dismiss reports in the Israeli media where Issaschar was portrayed as “exhausted” and not able to hold on any longer,[30] as well as suffering from intimidation and isolation.[31]

The Israeli media attention surrounding the Issaschar affair culminated in January 2020 during President Putin’s visit to Jerusalem for the World Holocaust Forum, which commemorated the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp. Prior to Putin’s visit, it was announced that he would meet with Issaschar’s mother,[32] causing the Israeli media to focus disproportionately on the fate of Issaschar rather than on any other aspect of the visit. It is likely that Putin had already decided to pardon Issaschar before his visit to Israel, but chose to postpone this procedure until after the Forum.[33] During the Forum, Putin was able to present Russian politicized narratives of the Second World War,[34] which created controversies with Eastern European leaders (the Polish president refused to attend, and Ukraine’s president decided in the last moment not to enter the hall during Putin’s speech).

A week later, Putin pardoned Issaschar, and Netanyahu flew to Moscow to escort her home. Although Russian and Israeli government officials claimed that Issaschar was pardoned on humanitarian grounds, reports indicated that a deal had been made between the two countries. Allegedly, Israel agreed to help with the Russian Orthodox Church’s claim over ownership of the St. Alexander Nevsky Church in Jerusalem, a Russian Orthodox Christian site near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, that was under the control of a Christian German NGO, much to Moscow’s displeasure.[35] Other concessions reportedly included Israel’s implicit support for the Russian narrative of the Second World War, which was evident from the World Holocaust Forum, and providing positive media coverage of Putin’s visit to Israel. Thus, Issaschar’s case became an effective tool for advancing political goals important to Russia.

Russia’s Information War in Israel

We have identified four ways in which the Russian actors’ involvement in the Issaschar case constitute a manipulative and deceitful intervention in the Israeli information space, resembling an “information war.”

- Hijacking the Israeli Public Agenda

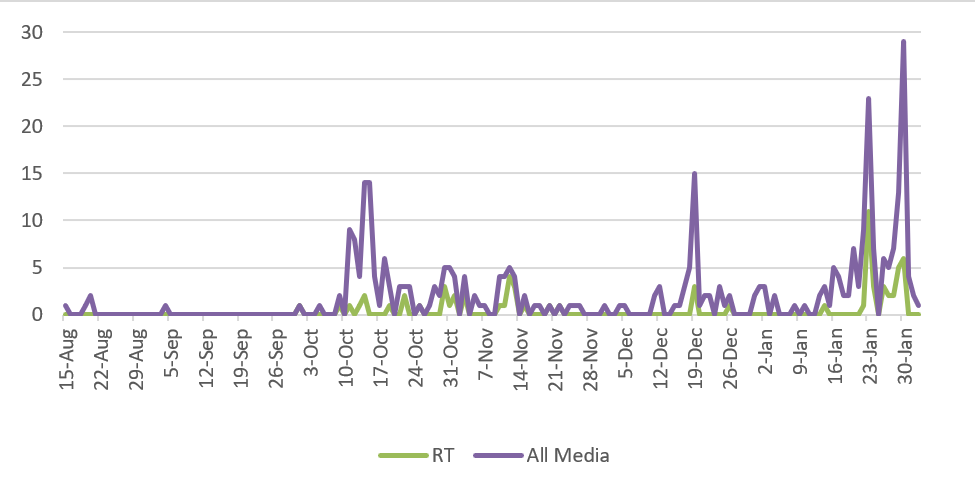

One of the most significant findings of our media survey was that RT’s report linking Issaschar to Burkov resulted in a notable increase in her coverage in Israel. Prior to RT’s report, the Israeli media had shown little interest in Issaschar. From her arrest on April 9, 2019, until the news about the potential swap offer broke in Israel on October 11, 2019, she had been barely mentioned in Israel’s leading media outlets.

The RT story that linked Issaschar and Burkov clearly affected the Israeli media space. As the original story about the swap on RT was published in Russian on October 9, it took about 48 hours for the news to reach the largely Hebrew-dominated Israeli media.[36] From the morning of October 11 until her release, the Israeli media reported on Issaschar almost daily. The week following the news of a possible swap, Mako published 33 reports about Issaschar, and Ynet published 25 (see Figure 3). Symbolically, only when Ynet wrote on Issaschar’s alleged connection to Burkov did the website generate a news tag with her name—signaling that only at that point did she become a news item worthy of tagging.

Figure 3. Media Coverage of Issaschar’s Case (August 2019–January 2020)

The chart shows that Issaschar’s case gained attention from the Israeli media only in response to RT coverage. This evident increase in media reporting on Issaschar could have been circumstantial (due to an Israeli interpretation of RT’s reports as an official Russian request for a swap). Yet, RT did not deal with this story beforehand, and its in-depth coverage is hard to interpret as reporting of a newsworthy item. It looks more likely as an attempt to direct public attention to a hitherto marginal event. A closer look uncovered a long list of additional manipulative activities by RT, substantiating the claim that its role in the affair was to assist in an information operation.

- The Backpacker and the Hacker—Comparable Victim Images

RT’s manipulation of the media’s agenda was in positioning Burkov and Issaschar in very similar terms—both as victims of unjust legal treatment. A detailed account of Burkov’s grievances presented the artificial, almost random link between the two cases. RT and the Russian Embassy in Tel Aviv claimed that Burkov was an “ordinary person” whose only chance for justice was “hope for an exchange” with Issaschar because he had fallen victim to unjust treatment just like her.[37]

This was manipulative, as it equated two very different legal realities. Issaschar was charged with a crime she had no way of committing (she could not have smuggled drugs into Russia because she never intended to enter the country but was only in transit). Burkov was subject to a year’s-long FBI investigation for multiple online frauds and thefts, which amounted to $20 million dollars. The evidence against Burkov was reviewed by several Israeli courts and found to be of a sound legal standard.[38] These details, omitted from RT’s reports, created a misleading portrayal, in which he and Issaschar were comparable victims. By doing so, RT helped the Russian government legitimize Issaschar’s arbitrary detention.

- Plausible Deniability of the Russian Government’s Involvement

RT also presented the origins and nature of the proposal to exchange Issaschar and Burkov in a manipulative way, claiming that the instigators and lobbyists of the swap were Burkov’s family and friends. For example, RT interviewed Burkov’s sister, Natalya, and his alleged friend—the enigmatic Konstantin Bekenshtein, who had left public comments in August and September. RT suggests that these two independently and voluntarily initiated and lobbied for the swap.[39] This falsely framed the proposal as a humanitarian exchange when RT must have known that the swap was initiated by the Russian government and was much closer to a hostage-taking event, where a civilian was held in custody and promised to be released only after their country satisfied their demands. In doing so, they obscured the Russian government’s role in initiating the request and allowed the Kremlin plausible deniability.

RT knew the true source of the deal since Russian officials most likely briefed its staff about it. We deduce it from the fact that in October 2019, Israeli and Russian officials were the only reliable sources who knew about the swap idea. Israeli officials were unlikely to share this with RT since they had kept it secret even from Issaschar’s family. Russian officials, by contrast, had the knowledge, motivation, and access to RT to make the story public at that time (48 hours before Issaschar’s sentencing) to pressure Israel. There is nothing wrong with RT publishing such an intriguing story without disclosing their sources or with Russian officials leaking the story at a time convenient for them to pressure Israel. However, RT’s decision to publish a false claim about the provenance of the information was more problematic.

Contrary to RT’s narrative, Bekenshtein was in no position to promote a deal between Israel and Russia. RT’s narrative was also inconsistent with Bekenshtein’s early comments on Mako and to Issaschar’s family, where he claimed that “the Russians” were seeking the exchange and that Issaschar was held captive in Russia.[40] RT did not only conceal their sources, which is a common journalistic practice, but it also promoted a false version of reality that obscured the state-backed nature of the event where Russia attempted to leverage Issaschar’s imprisonment against Israel, as confirmed by senior Israeli officials.[41]

- Daniil, the Activist, and Lomakin, the Journalist

An incident involving RT’s Lomakin raises further suspicion that he was working to influence the Israeli media discourse and exert pressure on the Israeli government. Lomakin’s behavior points to possible state-backed actions aimed at influencing the Israeli information space. He was allowed by the Russian goernment to visit Issaschar in prison and reported a version of events that was not truthful but convenient for the Russian state. Moreover, as he was not investigating Issaschar undercover, he had no reason to hide his affiliation with RT from her. Hence, this was closer to a pattern of an influence campaign, where he deceived Issaschar and Israeli journalists to spread false information that was flattering to the Russian penitentiary system.

Reputational Damage to Russia—How an “Information War” Can Backfire

The limits of this information campaign should also be considered. After RT helped the Russian government establish plausible deniability, it also positioned Putin’s subsequent pardon of Issaschar as a benevolent and humanitarian act. After Burkov was extradited, RT’s reporting on the case noticeably diminished. RT resumed reporting on Issaschar around Putin’s visit to Israel in January 2020. In its reports about the clemency, RT underlined that the expected pardon was a benevolent act by Putin, which corrected the excesses of the Russian judicial system.[42] Putin reflected on both points in his explanations for the pardon, which RT described as “guided by the principles of humanity.”[43] Putin described Issaschar as “lucky,” again highlighting his merciful disposition toward the case.[44]

When considering the impact of RT’s influence campaign on the Israeli media space, its successes were mixed. Although it helped maximize pressure on Israel during a politically sensitive time and achieved some important returns for the Kremlin, Russia also suffered reputational damage in Israel. The Israeli media discourse around Issaschar developed along the lines of the most powerful political discourse in Israeli society—the captives/hostages discourse, in the IDF camaraderie spirit of “no one gets left behind.” Following RT’s linkage between Issaschar and Burkov, she was branded as a “captive,” which drew an emotional outpouring of support for her and her family. For instance, Ynet’s celebrity section reported that Israeli celebrities supported her under the title “We must not abandon her.”[45] Netanyahu also echoed this discourse in a public letter to Issaschar: “We do not abandon any person to their fate.”[46] But as part of the same discourse, Putin was depicted as a “hostage-taker” and villain, with such associations causing reputational damage for Russia in Israel.

Furthermore, RT’s framing of a possible humanitarian exchange failed to gain support for a Burkov–Issaschar deal. While public sympathy was largely with Issaschar and her family, a course of action that would have angered Israel’s closest ally, the United States, unsurprisingly failed to gain support. Israel’s strategic partnership with the US was evidently a strong and underlying political discourse in Israel.

Conclusion

The Issaschar affair is a relatively early but important example of the intensifying modus operandi of the Putin regime, which involves hostage-taking of foreign civilians on Russian soil to leverage them for high-level political quid-pro-quo. Other high-profile arbitrary detentions of foreign citizens, all Americans, by the Russian authorities include businessman Paul Whelan, basketball player Brittney Griner (who was released in exchange for Russian arms dealers Viktor Bout), and journalist for the Wall Street Journal Evan Gershkovich.[47] The information domain plays a prominent role in this modus operandi, as domestic public pressure is essential for ordinary civilians who have been imprisoned by the Russian authorities to be considered eligible for a high-level political intervention and exchange.

While this case was not initially considered an information operation, the Russian holistic definition of information war suggests otherwise. The Russian understanding of the media space as a deeply securitized arena allowed the Kremlin to use various actors, with RT among them, to influence Israeli public discourse to pressure the Israeli government to negotiate with Russia.

This article explores the contours of an informational-psychological Russian campaign in Israel, where Issaschar’s imprisonment and release were used by RT (a government-owned and operated entity) to advance Russian state goals. Using the conceptual framework of information war, we traced how a civilian Russian state-backed news agency triggered an affair that had outsized significance for Russian–Israeli relations and Israeli internal politics for five months. This approach gave the Kremlin flexibility and maneuverability as it exerted pressure on the Israeli government and society. As a result, even in the face of Israeli defiance to release Burkov in exchange for Issaschar, Russian pressure on Israel continued and eventually led to Israeli compromises vis-à-vis the Kremlin.

This research contributes to the current debate on Russian influence operations in several ways. First, it highlights this interesting example of an ongoing broad and varied Russian psychological-informational effort that has not received enough attention in the context of Russian–Israeli relations. Second, the Issaschar affair should have served as an early warning sign to the Israeli government and authorities that relations with Russia were about to deteriorate. This became more evident in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine, and even more so since October 2023, after the Kremlin embraced Hamas’ narrative in the Gaza war. Further deterioration in the relationship can be expected and Israel should take appropriate measures to address this threat.

This brings us to the final contribution of this article, namely, calling attention to Israeli lack of preparedness for Russian influence activities. Israel has been slow to address the comprehensive nature of the Russian information war.[48] In contrast to many Western countries that blocked RT’s broadcasting following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, RT, along with other state-backed Russian news outlets, continue to operate freely in some parts of the world, including Israel. As a result, RT is able to participate in influence efforts under the guise of a media outlet, putting Israel at risk of malign Russian influence. Israel should develop an integrated government–civil society strategic approach to counter and combat malign influence operations by Russia and other actors. This process should begin as soon as possible and include learning, policy review, and the reallocation of resources and efforts.

_________________

[1] The authors would like to thank Dmitry Adamsky, Itai Brun, Yaakov Falkov, Ofer Fridman, Dudi Siman-Tov, Yelena B., and especially Vera Tolz, for their thoughtful comments and wise suggestions. We are grateful to a member of Issaschar’s family and the journalists who covered the story in Israel who kindly helped us to reconstruct the timeline of the affair and to retrieve important details. We also thank Daniela Tsirulnik for research assistance.

[2] Itamar Eichner and Itai Blumenthal, “Na’ama Issaschar in Ben-Gurion Airport: ‘Thanks to Everyone, Still Shocked from This Situation,’” [in Hebrew] Ynet, January 30, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5669377,00.html.

[3] Additionally, we researched the general coverage of the Issaschar and Burkov in Russian, Hebrew, and English media and social networks, starting from Burkov’s arrest in Israel in December 2015 until Issaschar’s release in January 2020. We also conducted interviews with Issaschar’s family, journalists who covered the story in Israel, and former Israeli public officials. Studying the impact of the Issaschar affair on social media discourse is beyond the scope of this research

[4] For further reading on RT, see Mona Elswah and Philip N. Howard, “‘Anything that Causes Chaos’: The Organizational Behaviour of Russia Today (RT),” Journal of Communication 70, no. 5 (October 2020): 623–645, https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa027; Vera Michlin-Shafir, Dudi Siman-Tov, and Nofar Sha’ashu’a, “Russia as an Information Power,” [in Hebrew] Modi’in Halakha uMa’ase 4 (April 2019); Vera Tolz, Stephen Hutchings, Precious N. Chatterje-Doody, and Rhys Crilley, “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency: Russian Television Coverage of the Skripal Poisonings,” Journalism 22, no.12 (July 2020), https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920941967.

[5] Nadav Eyal, “Intelligence Officials in Israel Demanded From the Russians: Stop the Online Influence Operations,” [in Hebrew] Ynet, July 21, 2023, https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/hks3ymd9h.

[6] Asaf Liberman, “Bargaining Chip – the Full Story Behind the Imprisonment of Na’ama Issaschar,” [in Hebrew] Kan 11, October 18, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQ554jKQYeA&t; Carmel Libman, “Issaschar family on Hacker Extradition: ‘Justice Minister’s Decision Is Inhuman,’” [in Hebrew] Mako, October 30, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/news-world/2019_q4/Article-53dfae6923e1e61027.htm; Michal Peylan, “Na’ama on Her Way to Freedom,” [in Hebrew] Mako, January 29, 2020, https://www.mako.co.il/news-world/2020_q1/Article-340db61f633ff61026.htm.

[7] See Dmitry (Dima) Adamsky, Cross-Domain Coercion: The Current Russian Art of Strategy (Paris: IFRI Security Studies Center, 2015); Yaacov Falkov, “Russian Information Warfare in the Ukraine War,” [in Hebrew] Israel Intelligence Heritage & Commemoration Center (IICC), March 14, 2023, https://www.intelligence-research.org.il/post/influence-russia-ukraine; Ofer Fridman, “Conceptualization of Foreign Influence and Foreign Interference,” [in Hebrew] Israel Intelligence Heritage & Commemoration Center (IICC), January 4, 2024, https://www.intelligence-research.org.il/post/fridman-january-2023; Ofer Fridman, “‘Information War’ as the Russian Conceptualisation of Strategic Communications,” The RUSI Journal 165, no. 1 (2020): 44–53, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2020.1740494; Tolz, Hutchings, Chatterje-Doody, and Crilley, “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency”; Thomas Rid, Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020).

[8] Dmitry (Dima) Adamsky, “From Moscow With Coercion: Russian Deterrence Theory and Strategic Culture,” Journal of Strategic Studies 41, no. 1–2 (2018): 33–60, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402390.2017.1347872.

[9] Mason Clark, Russian Hybrid Warfare (Washington DC: Institute for the Study of War, 2020), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26547.1.

[10] Rid, Active Measures.

[11] Dmitry (Dima) Adamsky, “Deterrence à la Ruse: Its Uniqueness, Sources and Implications,” NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies )2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-419-8_9.

[12] Nina Jankowicz, How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2020).

[13] RT’s activities have received the most attention from media studies scholars, who argued that Russian media campaigns should be considered within the framework of global media studies. See Tolz, Hutchings, Chatterje-Doody, and Crilley, “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency.” They have pointed out that within the Western discourse, the term “information war” lacks sufficient theorization and remains limited in explaining Russia’s activities. See also Vitaly Kazakov and Stephen Hutchings, “Challenging the ‘Information War’ Paradigm: Russophones and Russophobes in Online Eurovision Communities,” in Freedom of Expression in Russia’s New Mediasphere, ed. Mariëlle Wijermars and Katja Lehtisaari (London: Routledge, 2019), 137–158. Furthermore, numerous studies about RT’s activities raised doubts about its ability to reach and influence audiences in Western countries, with its viewership remaining largely marginal. See Joshua Benton, “How Many People Really Watch or Read RT, Anyway? It’s Hard to Tell, but Some of Their Social Numbers Are Eye-Popping,” Niemanlab, March 2, 2022, https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/03/how-many-people-really-watch-or-read-rt-anyway-its-hard-to-tell-but-some-of-their-social-numbers-are-eye-popping/; Tolz, Hutchings, Chatterje-Doody, and Crilley, “Mediatization and Journalistic Agency.”

[14] Fridman, “‘Information War.”

[15] Issaschar returned to Israel from a long trip as part of a large group of backpackers. The only odd thing, she recalled, was that while boarding the plane in India, she was moved from her prebooked flight to a later transit flight from Moscow to Tel Aviv, which effectively separated her from the group. From a personal conversation with a member of Issaschar’s family.

[16] A month later, the Moscow prosecutor’s office aggravated the charges from illegal possession of drugs (punishable by up to three years in prison) to drug smuggling (punishable by up to 10 years). See Nikita Sologub and Elizaveta Pestova, “She Did not Understand, What Does it Mean - Being Arrested in Russia. The History of Na’ama Issaschar, Who Wanted to Get Back to Israel by Transit Flight through Moscow, but Got Detained due to Claims of Drug Smuggling,” [in Russian] Mediazona, October 10, 2019, https://zona.media/article/2019/10/10/naama.

[17] Nina Fox, “Hundreds of Israelis Are Still Imprisoned Abroad,” [in Hebrew] Mako, January 30, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5669482,00.html.

[18] Tom Cohen and Amit Waldman, “Mother of the Jailed Israeli in Russia: ‘I Hope the Government Will Get Her Out, I Was not Allowed to Get Close to Her,” [in Hebrew] Mako, August 15, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/news-world/2019_Q3/Article-418b7bbe9959c61026.htm.

[19] “An Israeli Is Imprisoned in Russia,” [in Hebrew] Mako, August 20, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/news-israel/2019_q3/Article-2fd3d9aa90eac61027.htm; Liza Rozovsky, Bar Peleg, and Noa Landau, “The Friend of the Russian Hacker: I Turned to the Issaschar Family After He Was Told About the Connection Between the Two,” [in Hebrew] Haaretz, October 11, 2019, https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/law/.premium-1.7968356.

[20] It is not clear whether Netanyahu and his aides knew in advance, before asking Putin to release Issaschar, that his price tag would be Burkov. Israeli officials present contradictory versions two years after the events. In 2022, Netanyahu’s national security advisor, Meir Ben-Shabbat, claimed that a demand to extradite Burkov to Russia in connection with the fate of Issaschar was mentioned by his Russian counterparts only after Netanyahu raised Issaschar’s name before Putin. A similar sequence of events was described by a senior official from the Israeli Ministry of Justice who dealt with Burkov’s extradition to the United States: He had not heard the name Na’ama Issaschar before Netanyahu had asked Putin to release her. The authors assume that if the Israeli officials had understood in advance that the Russians would demand to trade Burkov for Issaschar, Netanyahu would not necessarily have asked Putin for this humanitarian gesture, and it might have been addressed at a bureaucratic level. See Liberman, “Bargaining Chip,” 21:10–21:33, 23:20–25:36.

[21] Daniil Lomakin, “She Didn’t Even Go Through Customs: Foreigner Is Suspected of Drug Smuggling During the Transit Flight,” [in Russian], RT na Russkom, October 1, 2019, https://ru.rt.com/efhw.

[22] Daniil Lomakin, “Arrested in a Standard USA Scheme: Russian Citizen Detained due to an American Request Is Sitting Four Years in an Israeli Jail,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, October 9 2019, https://russian.rt.com/russia/article/675668-ssha-izrail-rossiyanin-ekstradiciya.

[23] The press release confirmed that Netanyahu raised Issaschar’s case with Putin at least twice—in a meeting between the two in Sochi, Russia, on September 15, and in a phone conversation between the two on October 4. Apparently from their quick response, the Israeli side was aware of the Russian swap request before the RT publication and tried to deal with the issue through diplomatic channels, treating it as highly confidential and not even informing Issaschar’s family. See “An Announcement by the Prime Minister’s Office Considering Na’ama Issaschar,” Israeli Prime Minister’s Office Spokesman, October 11, 2019, https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/news/spoke_naama111019; Conversation with a relative of Na’ama Issaschar, 2020.

[24] Yaron Avraham and Carmel Libman, “'Special Force to Bring Na’ama Home': After the Recording – Parties’ Leaders Under Pressure,” [in Hebrew] Mako, October 13, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/news-world/2019_q4/Article-cf9f1d57b81cd61027.htm.

[25] Anna Rayva-Barsky, “Journalists Pretending to Be Human Rights Activists Interviewed Na’ama Issaschar: I Don’t Believe That I’m That Famous,” [in Hebrew] Maariv, October 23, 2019, https://www.maariv.co.il/news/world/Article-725316.

[26] Daniil Lomakin, “I Hope That Publication Will Help: Human Rights Activists Had Visited the Incarcerated Israeli Na’ama Issaschar Convicted of Drug Smuggling,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, October 22, 2019, https://ru.rt.com/ek97.

[27] Hen Zender and Roni Shchuchensky, “The Activist Who Met Na’ama Issaschar: She’s in Good Shape and Practices Yoga,” [in Hebrew] Channel 13 TV, October 23, 2019, https://13news.co.il/item/news/politics/state-policy/naama-activist-interview-916940/.

[28] RT, “RT Journalist Becomes a Member of the Public Observatory Commission,”[in Hebrew], RT na Russkom, October 8, 2019, https://ru.rt.com/eh1q.

[29] Editorial, “New Membership of Moscow, Moscow Region and Saint-Petersburg Public Observatory Commissions Excludes Several Human Rights Activists, Who Visited Detained Political Prisoners,” [in Russian], Novaya Gazeta, October 8, 2019, https://novayagazeta.ru/news/2019/10/08/155967-v-novyy-sostav-onk-moskvy-podmoskovya-i-peterburga-ne-voshli-neskolko-pravozaschitnikov-naveschavshih-v-sizo-politzaklyuchennyh.

[30] Noa Lavie, “Na’ama Issaschar During Her Mother’s Visit in Jail: Thankful for all the Support,” [in Hebrew] Ynet, October 14, 2019, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5607096,00.html.

[31] Niv Raskin, “Who’s Threatening Yaffa Issaschar? I Turned Down a Proposal and Then Got a Message That Shook Me. I’m Frightened,” [in Hebrew] Mako, November 17, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/tv-morning-news/articles/Article-ad943f99f187e61027.htm.

[32] “Putin Will Meet in Israel With the Mother of Issaschar, Who Was Convicted in Russia,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, January 22, 2020, https://ru.rt.com/f8d1.

[33] During his meeting with Yaffa Issaschar, together with Netanyahu and the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Putin reassured her of a positive solution for her daughter’s release, saying “everything is going to be OK.” See Yaron Avraham and Yair Sherki, “On the Way to Na’ama’s Release. Putin Said to the Press: ‘Everything is Going to Be OK,’” [in Hebrew] Mako, January 23, 2020, https://www.mako.co.il/news-israel/2020_q1/Article-472c58db5b1df61026.htm.

[34] TOI Staff, “ Yad Vashem Apologizes for Distortions Favoring Russia at Holocaust Forum,” Times of Israel, February 3, 2020, https://www.timesofisrael.com/yad-vashem-apologizes-for-distortions-favoring-russia-at-holocaust-forum/.

[35] Itamar Eichner, “The Moment of Truth for Na’ama Issaschar: What Do the Russians Want?” [in Hebrew] Ynet, January 22, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5664164,00.html; Itamar Eichner, “Na’ama on the Prime Ministers Plane: This is the Quid-Pro-Quo Given to the Russians,” [in Hebrew], Ynet, January 30, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5669208,00.html; Liberman, “Bargaining Chip.”

[36] Although Israel has a large Russian-speaking community, Hebrew dominates the domestic media, and there are only a handful of Russian-speaking prominent journalists. On October 10, 2019, RT posted a shorter version of the story about the swap on its English language website, and on October 11, the morning after, the story broke out in the Israeli media. See RT, “‘I’m an Average Man’: Russian Man Faces Extradition from Israel to the US on Hacking Charges,” October 10, 2019, https://on.rt.com/a34m.

[37] Daniil Lomakin, “Arrested in a Standard USA Scheme: Russian Citizen Detained due to an American Request Is Sitting Four Years in an Israeli Jail,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, October 9, 2019, https://russian.rt.com/russia/article/675668-ssha-izrail-rossiyanin-ekstradiciya.

[38] Israeli Supreme Court of Justice, “Alexei Burkov Against the Minister of Justice and Attorney General,” [in Hebrew] November, 2019, Case 7272/19, https://supremedecisions.court.gov.il/Home/Download?path=HebrewVerdicts%5C19%5C720%5C072%5Cv05&fileName=19072720.V05&type=4.

[39] Lomakin, “Arrested in a Standard USA Scheme.”

[40] Noa Landau, Bar Peleg, and Josh Breiner, “‘Disproportionate’ Sentence for Israeli-American After Russian Request to Release Hacker Denied,” Haaretz, October 11, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israeli-source-moscow-pressed-to-release-hacker-in-exchange-for-detained-israeli-1.7967753; Niv Raskin, “Sister of Na’ama Issaschar, Jailed in Russia: The Girl Is Devastated. She Has Lost the Hope. It Is a Nightmare,” [in Hebrew] Mako, September 4, 2019, https://www.mako.co.il/tv-morning-news/articles/Article-a53834871bafc61027.htm.

[41] Liberman, “Bargaining Chip,” 26:50–29:50.

[42] Roman Shimayev, “Guided by the Principles of Humanity: Putin Has Pardoned the Israeli Na’ama Issaschar,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, January 29, 2020, https://ru.rt.com/fac7.

[43] Marina Yudenich, “About Mercy,” [in Russian] RT na Russkom, January 23, 2020, https://ru.rt.com/f8oc.

[44] Itamar Eichner and Eti Abramov, “A Kiss from Netanyahu: Na’ama Issaschar is on the Plane on its Way to Israel,” [in Hebrew] Ynet, January 30, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5669172,00.html.

[45] Yoni Froim, “Celebrities Support Na’ama Issaschar: We Should not Abandon Her,” [in Hebrew] Pnai Plus (Ynet Group), October 15, 2019, https://pplus.ynet.co.il/rechilut/article/5607531.

[46] Itamar Eichner, “Netanyahu in a Letter to Na’ama Issaschar: We do not Abandon Anyone,” [in Hebrew] Ynet, January 13, 2020, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5659066,00.html.

[47] Natasha Bertrand, Katie Bo Lillis, and Jennifer Hansler, “US Proposal to Russia to Free Whelan and Gershkovich Included Swapping a Number of Suspected Russian Spies, Sources Say,” CNN, December 5, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/12/05/politics/state-department-whelan-gershkovich-proposal/index.html.

[48] Yaacov Falkov, “Russian Information Warfare in the Ukraine War,” [in Hebrew] Israel Intelligence Heritage & Commemoration Center (IICC), March 14, 2023, https://www.intelligence-research.org.il/post/influence-russia-ukraine.