Publications

INSS Insight No. 1555, February 13, 2022

A widespread protest is underway in the haredi (ultra-Orthodox) society in Israel against the reform intended by the Minister of Communications regarding “kosher” cell phones: transparency in the decisions of the Rabbinical Committee for Communications and the abolition of the preliminary digits that identify kosher telephone numbers. Most of the sub-communities and circles in the haredi society are united in the protest against the intended reform, in particular the abolition of the preliminary code. This article reviews the perceived threat of the internet in ultra-Orthodox society and examines the effectiveness of actions taken so far by the community and its leaders to curb threats to its singularity and segregation. It contends that most members of the ultra-Orthodox community in Israel use the internet according to restrictive patterns approved by the leadership, and that outside coercion aimed at joining the community and the general public will not succeed.

The complex relationship between the haredi (ultra-Orthodox) and general society in Israel is based primarily on the haredi self-perception as authentic Judaism positioned against modern society. The ultra-Orthodox choose to separate from Israeli society in many areas, with the very separation being a prominent sign of their self-perception. In order to preserve segregation, the ultra-Orthodox community has built "walls" around it that are supposed to divide and differentiate it from other communities. This deliberate separation is manifested in diverse areas, including separate neighborhoods and education systems, a sectoral press, the non-identification with national symbols, the refusal to enlist in the IDF, particular modes of dress, and attempts to avoid unnecessary contact with the non-haredi population.

Over the years, the walls of segregation have been challenged by external and internal attempts to join the ultra-Orthodox and the general population. In response, the haredi leadership focuses on strengthening the walls, while following and monitoring the community's updated needs and creating "kosher" alternative practices. Thus, in the face of the threat inherent in the written and broadcast media, they created alternatives in the form of ultra-Orthodox radio and press. This too has been the modus operandi vis-à-vis the internet.

The internet is perceived as a particularly powerful threat: it is a mass platform, available and attractive, allowing private and anonymous access to messages, texts, images, and external and unsupervised interactions, with content that is overwhelmingly challenging. It is cast as a formidable system that has the power to break down the walls of segregation, both due to exposure to inappropriate content and due to exposure to messages that criticize the ultra-Orthodox leadership – in other words, the very structure of the entire community.

In response to these threats, the haredi community declared war on internet use. At first, the rabbis banned the use of the internet outright. Over the years, as the daily need for the internet increased, the rabbis realized that they had to find a practical solution that would enable the daily existence of the ultra-Orthodox alongside the internet. Thus at the same time as the condemnation intensified, the rabbis allowed certain people, on an individual basis, to use the internet for livelihood purposes, under various restrictions. Later, as the use of the internet became almost a necessity for large sections of the public, private initiatives developed that offered filtered internet infrastructures for home computers and cell phones. These infrastructures were permitted for use for livelihood purposes only, when it was emphasized that the kosher and filtered internet should not be used in public and used only to a minimal extent.

At the same time, the Rabbinical Committee for Communications was established, as an organization that developed (together with the cellular providers) kosher mobile phones. The telephone numbers of those subscribing to these programs were assigned a specific preliminary code, designed to identify the device as kosher. These devices are blocked for SMS, video, radio, camera, and internet use. The kosher devices are also blocked for bilateral contact with devices defined by the organization as containing unacceptable content. Cellular devices have likewise been developed that are used for livelihood purposes, and although they have access to the internet, this is limited to e-mails, WhatsApp, and specific websites approved by the rabbis.

In recent years, much criticism has been leveled at the Rabbinical Committee for Communications for allegedly acting arbitrarily and for reasons that are not always relevant to the matter. This criticism represents the background to the initiative of the Minister of Communications, Yoaz Handel, from August 2020, to reform the kosher cellular field. This includes two major changes: the first, for transparency purposes, requires the Rabbinical Committee to publicly publish the list of blocked lines, with an explanation for the reason for the block. The second change requires allowing kosher SIM cards to work with non-kosher devices and vice versa. The Minister of Communications explains the necessity of the reform in the widespread use of the internet in the ultra-Orthodox community (according to him, over 50 percent). The rabbis, on the other hand, claim that most of the ultra-Orthodox who use the internet do so in a limited and careful manner for the sake of earning a living only, and the minister's decision is based on data that do not accurately reflect reality.

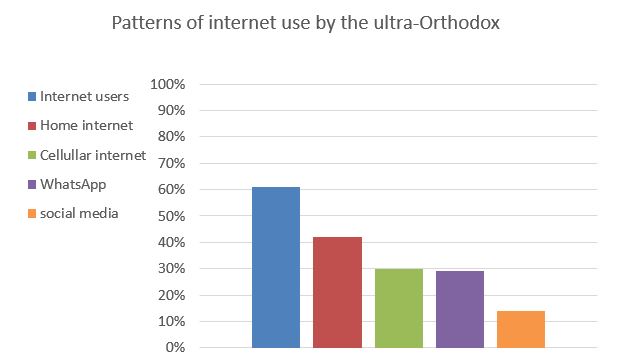

Indeed, there seems to be a different interpretation by the parties of the data on ultra-Orthodox use of the internet. The CBS social survey from 2020 found that 61 percent of the ultra-Orthodox use the internet. The Minister of Communications states that given this widespread distribution, there is no place for continuing the kosher cellular programs, and that the rabbis are not aware of the high percentage of ultra-Orthodox who use the internet. However, a careful perusal of the data shows that there is a fundamental difference between the home internet and the mobile internet. According to the CBS, 70 percent of the haredi community do not have a cell phone with internet access and 85 percent completely abstain from using social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn (Figure 1). Moreover, most of the internet use occurs on a home infrastructure, where, according to the Askaria Institute (2021), a research company specializing in the haredi sector, about 78 percent of these infrastructures are filtered and restricted to exclusive access to necessary sites or Torah sites. According to this data, presumably most of the ultra-Orthodox who use the internet do so mainly for livelihood purposes.

Figure 1: Patterns of internet use by the ultra-Orthodox (Social Census Survey, 2020)

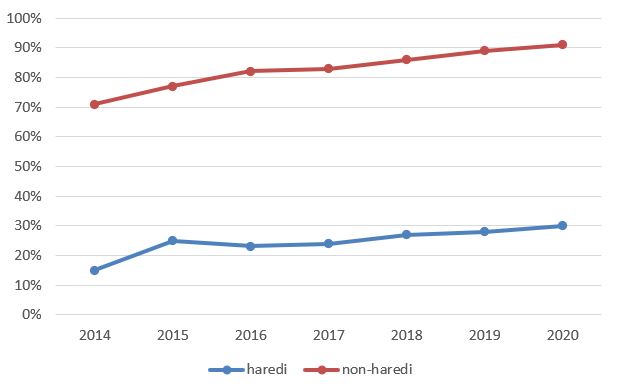

In the ultra-Orthodox community, this data is decisive. The ultra-Orthodox leadership does not ignore the need of community members to use the internet, and the rabbis do not deny the fact that the internet is a necessary tool for day-to-day life. As early as 2014, Rabbi Kanievsky and Rabbi Karelitz permitted the use of kosher cellular internet for livelihood purposes, a step that opened the door for the purchase of kosher internet services for those ultra-Orthodox who follow their rabbis’ directives but need the internet for their livelihood. Therefore, the very use of the internet in its limited configuration does not indicate, according to the ultra-Orthodox, a breach of the walls of separation. Moreover, prior to the rabbinical allowance, the percentage of ultra-Orthodox who used cellular internet was 15 percent, while after the permit was issued, it doubled and now stands at 30 percent (Figure 2). Thus, today only 15 percent of the ultra-Orthodox use social media networks that do not heed the rabbis' directives.

Figure 2: Use of the cellular internet, 2014-2020 (CBS, 2020)

Therefore, it appears that so far the social strategies and technological practices adopted by the rabbis have proved effective. The ultra-Orthodox community succeeds, for the most part, in continuing to differentiate itself as per its ideology, using intelligent and agreed-upon technologies available for the purpose of creating the necessary separation. In the face of these, the steps by the Minister of Communications, and in particular, the demand to adapt a SIM with a kosher number to non-kosher devices has provoked harsh negative reactions from the ultra-Orthodox leadership, which went on to define it as a "more serious a threat than even the Holocaust." For them, this move will abolish the kosher nature of cell phones and create a situation in which the ultra-Orthodox community will not be able to characterize the 'identity card' of its members, and thus the ultra-Orthodox wall of separation will be punctured.

Past experience has shown that like other minority groups, the haredi community radicalizes its positions in the face of attempts by the establishment to produce change and impose integration. Under these circumstances, it is doubtful whether forcing the abolition of the uniform preliminary code for kosher cell phones will succeed. Indeed, ways must be found to deal with transparency issues of the Rabbinical Committee, but this must be done without unduly violating the freedom of the ultra-Orthodox to uphold their principles. The very discussion, certainly an attempt to create a forced situation, only strengthens the wall of segregation and the suspicion of the ultra-Orthodox community toward the state establishment and the general public, particularly in current political circumstances, when the ultra-Orthodox are not partners in the coalition and most of them feel excluded. This development is inconsistent with the need to strengthen the already shaky social solidarity.