Publications

INSS Insight No. 1655, November 3, 2022

Over the last few months Hezbollah has waged an intensive cognitive campaign involving kinetic, diplomatic, and economic tools over the maritime border agreement between Israel and Lebanon, which would allow both countries, and not just Israel, to produce gas. With the announcement that an agreement was reached, Nasrallah and the leaders of Hezbollah declared they had achieved victory in this campaign against Israel. It is difficult to decide whose strategic achievements were greater in the current battle over the maritime border and gas pumping, including in the cognitive campaign, given that each side is convinced of its own achievements and presents different justifications for its stance. At the same time, there are those in Israel who see the results of the negotiations as a loss. This article explains the logic behind Hezbollah’s conduct and the characteristics of the cognitive campaign it conducted, in order to allow a better response to the organization during likely future confrontations.

The combined cognitive, kinetic, diplomatic, and economic campaign that Hezbollah waged since June 2022 over the demarcation of the maritime border between Lebanon and Israel aimed at two primary target audiences: the Lebanese public and the Israeli public. The campaign aimed at the Lebanese public unfolded against a background of a severe political and economic crisis, and increased public criticism of the organization as one of the parties responsible for the crisis. In Lebanese public discourse Hezbollah was charged that it prioritizes Iranian interests over Lebanese interests, and that in practice it dictates Lebanese foreign and security policy. There was also heightened criticism of the organization for maintaining its own military force. In light of this criticism, Hezbollah had to justify its continued maintenance of a weapons arsenal, shore up its political influence vis-à-vis its rivals, and validate its claim to be the “defender of Lebanon.”

Toward Israel, Hezbollah sought to strengthen the element of deterrence, while proclaiming it is not afraid of confrontation and is willing to take military actions if needed. Here, the organization's campaign, in which the cognitive element was dominant, aimed to create a sense of urgency and acute threat in Israel, by emphasizing its ability to harm strategic targets across Israel, including the Karish gas field and beyond.

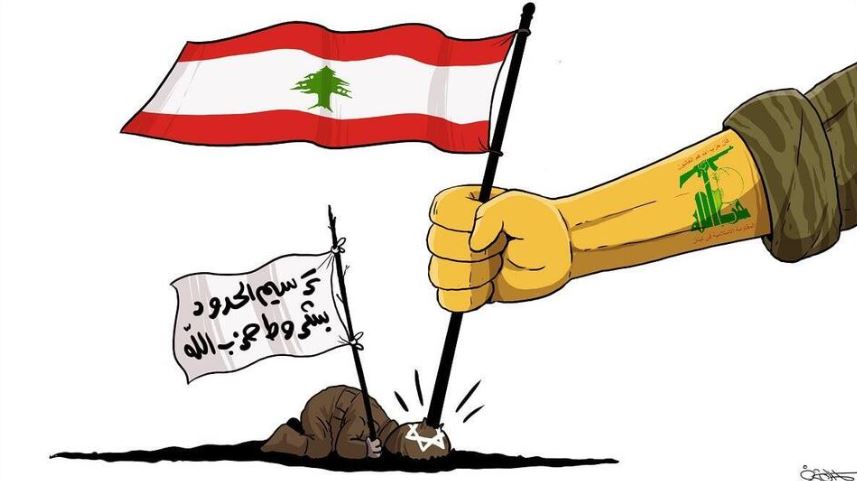

The campaign was waged primarily via speeches and interviews given by Nasrallah and other senior figures to supportive media outlets in Lebanon and on social media. In these statements, they emphasized the strategic dimension of the gas issue and its importance for solving Lebanon’s economic problems, and promoted the idea that only Hezbollah’s armed “resistance” can defend Lebanon’s interests and cause Israel to return what rightfully belongs to Lebanon in the Mediterranean. Inter alia, the organization disseminated videos and caricatures showing Israel’s fear of being attacked, including at the Karish rig. Senior Hezbollah figures also visited the Israeli border.

In addition, Hezbollah incorporated kinetic tools in its campaign. On two occasions, the organization launched unarmed UAVs toward the Karish platform (June-July 2022). The launches showed Hezbollah’s military capability, demonstrating that its precision weapons arsenal could harm Israel if it continues to ignore Lebanese interests at sea or anywhere else. Alongside fervent verbal threats, Hezbollah used the UAVs to demonstrate its willingness for escalation. It also sent a symbolic flotilla from the coast of Tripoli toward Israel’s territorial waters, as a challenge to the maritime frontier. Hezbollah reinforced troop deployments along the border, set up additional observation posts, and provoked IDF troops along the fence, and in a symbolic protest, Lebanese politicians who visited the fence threw stones into Israeli territory. Hezbollah also sent threatening messages via diplomatic channels.

A number of background conditions influenced Israel and Hezbollah’s management of the crisis in the negotiations, and contributed to the pressure that spurred Israel and Lebanon to reach an agreement in order to serve their interest in reducing the risk of deterioration into confrontation. Both Israel and Lebanon faced ticking political clocks – in Israel the Knesset elections, and in Lebanon the end of the president’s term. The date set in Israel for the start of drilling in Karish also spurred Hezbollah to threaten to derail the plan. The Israeli side was affected significantly by pressure from the US administration to reach an agreement: the US emphasized the global energy crisis and the understanding that this agreement is likely to incorporate Lebanon in gas production in the future, thus giving the region strategic stability, giving Lebanon a better economic future, and making it difficult for Hezbollah to take military steps against Israeli gas production in light of the price that Lebanon and the organization would pay for such steps.

Hezbollah managed a campaign of brinkmanship. Because Nasrallah believed that Israel was interested in an agreement and not in escalation, he declared that he was willing to risk military confrontation. For that reason, the organization fired unarmed UAVs, escalated its rhetoric, presented an ultimatum, and threatened to escalate its kinetic activity, although it refrained from carrying out that threat. Nasrallah repeatedly emphasized his preference for a negotiated solution over war and was careful to emphasize that he would respect a future agreement approved by the government of Lebanon, thus hedging his risks and allowing himself to take credit for the agreement that was reached.

In Hezbollah’s view, “it was victory by threatening war and not victory by war.” Its strategy was managed as a cognitive battle backed by threats and kinetic moves; this was also clearly expressed by Nasrallah’s speeches on October 27 and 29. In his words, the great victory belongs to “the government, the people, and the resistance.” The campaign his organization waged was intended to defend Lebanese rights, backed by both the threat of resistance weapons and deterrence of Israel from the use of force against Lebanon. It ended with an agreement that did not require Lebanon to commit to normalization with Israel.

Hezbollah’s primary success was in Lebanese public opinion, where it strengthened its claim to be a patriotic body defending Lebanon with its military power and assisting in the achievement of Lebanese interests, while taking a responsible approach. President Aoun praised it for doing so and for contributing to the success of negotiations. At the same time, the organization, in its view, succeeded in maintaining and even strengthening the deterrence equation vis-à-vis Israel, including on the maritime frontier.

In Israel’s view, on the other hand, mutual deterrence was maintained, Hezbollah’s threats were not carried out, a military confrontation did not take place, and no loss of human life or infrastructure damage occurred. The majority in Israel accepted the future economic gain, the reduced risk of escalation, and the potential for a quiet security environment around gas production, while planting the seeds of political-security understandings with Lebanon in the future.

At the same time, overt Israeli cognitive activity was minimal and apparently did not take advantage of the potential to damage Hezbollah’s image within and beyond Lebanon, by emphasizing its role as a warmonger that could have brought disaster on an already-collapsing Lebanon. It was also possible to emphasize Hezbollah’s negative role in preventing Lebanon from receiving international economic aid. Israel made do with warnings to Hezbollah from Defense Minister Gantz and outgoing Northern Command General Amir Baram that it should not test Israel and start a war, and in publicizing a flyover by Prime Minister Yair Lapid above the Karish oil rig.

It may be that Israel’s measured response to Hezbollah threats was part of a deliberate communications strategy intended to maximize the chances of reaching an agreement and a strategic-economic achievement in Israel’s view – even at the price of allowing Hezbollah to present the agreement as its own achievement. However, in the eyes of many in Lebanon and Hezbollah supporters in the regional “axis of resistance,” this approach allowed the organization to appear to win the cognitive campaign, and even in Israel to create a sense that the organization came out of the crisis with the upper hand.

Indeed, some political forces in Israel accept the perspective presented by Hezbollah that “imposing” the agreement on Israel is an achievement for the organization. According to these critics, Israel may have won important points in the current campaign vis-à-vis Hezbollah and in the broad regional context, but it may yet pay a long-term price for allowing Hezbollah to believe that the threats against Israel were what pushed it into the agreement. If it believes this, it will conclude that pressure and threats are likely to work against Israel in the future. In this view, Israel took a risk because Hezbollah’s sense of victory may nurture a false image of excessive power in light of what it views as Israeli weakness – which will encourage it to escalate provocations against Israel and proceed down a slippery slope toward violent confrontation.

With the end of the current crisis, the challenge facing Israel is how to prevent Hezbollah from interpreting what it perceives and presents as the victory of its campaign as Israeli weakness, which purportedly impelled Israel’s restrained and measured responses to Hezbollah threats. Israeli strategic clarity will require conveying to Nasrallah that Israeli preferred economic and political success over military response, even at the tactical price of allowing Hezbollah a partial cognitive achievement. At the same time, the challenge facing Israel, perhaps in the near future, will be to ensure that the element of deterrence is maintained vis-à-vis the organization, in light of likely provocations and frictions around remaining border dispute issues.