Publications

INSS Insight No.1495, July 13, 2021

Foreign Ministry Director-General Alon Ushpiz’s recent visit to Morocco represents an opportunity to inject momentum into the bilateral relationship, six months after the two countries announced the resumption of diplomatic ties. The kingdom’s recent outreach to Hamas, while disturbing, should be understood in the context of Morocco’s domestic political scene and Rabat’s desire to see Washington maintain American recognition of Moroccan sovereignty in the Western Sahara. Moving forward, Israel should focus its efforts on quietly and methodically nurturing ties with Morocco’s business community, a group essential for the normalization to succeed.

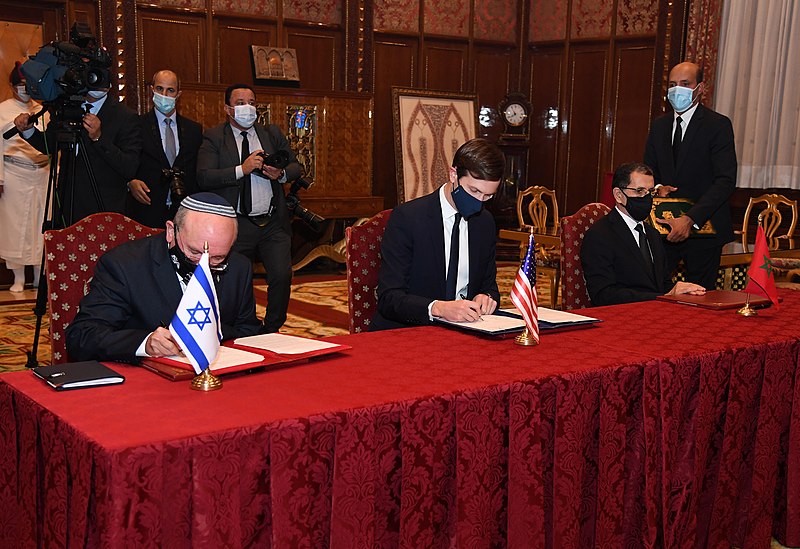

On July 6, 2021, Israel’s Foreign Ministry Director-General Alon Ushpiz traveled to Rabat, Morocco to meet his counterparts in the kingdom for what the Israeli Foreign Ministry described as a “political dialogue” between the two countries. Ushpiz's trip represents the first high-level visit of an Israeli diplomat to Morocco since the countries announced a resumption of diplomatic relations in December 2020. That agreement, brokered by the outgoing Trump administration, came alongside Washington’s controversial decision to formally recognize Moroccan sovereignty over the Western Sahara – a long-sought achievement for Rabat and a break from decades of US policy, which had largely deferred the matter to UN-led negotiations between Morocco and the Polisario, an Algeria-backed movement demanding independence for the territory since 1975. The price of Washington’s gift to Rabat was Morocco’s establishment of “full diplomatic relations” with Israel two decades after the kingdom had cut formal ties, against the backdrop of the second intifada.

Eschewing the term “normalization,” Moroccan officials instead presented the agreement as a return to the state of affairs in 2000, when liaison offices operated in the respective countries and Israeli tourists traveled regularly to the kingdom. Morocco’s decision to refrain from proclaiming full-scale normalization reflected both an effort to hedge against the possibility that the incoming Biden administration would not uphold the Sahara decision, and a desire on the part of King Mohamed VI, who is both Head of State and the kingdom’s chief religious authority, to retain his credibility concerning the Palestinian cause and especially the status of Jerusalem. (Mohamed VI chairs the Organization of Islamic Cooperation’s al-Quds Committee, a symbolically significant if functionally dormant body.) In March and April, statements out of Washington suggested the Biden administration would maintain the decision regarding the Sahara, even as it pushed for a resumption of talks aimed at achieving a political resolution to the conflict. With more or less continuity in US policy, Moroccan-Israeli ties began to develop, albeit much less visibly than the relationship between Israel and the United Arab Emirates.

With the eruption of hostilities between Hamas and Israel in May, Moroccan-Israeli normalization, which was already proceeding at a snail’s pace, faced its first serious test, as did the other normalization agreements signed in 2020 – between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, and Sudan. Much like its Arab peers, Morocco at first condemned Israel’s actions in Jerusalem, but then took a more muted stance once the conflict’s center of gravity shifted to Gaza – in a clear contrast to regional reactions during previous rounds of fighting in the Strip. Still, the momentum that had been building in the bilateral relationship slowed during Operation Guardian of the Walls, and in the ensuing weeks the kingdom sent mixed signals concerning its stance on normalization. Following the ceasefire, Moroccan Prime Minister Saad-Eddine El-Othmani, who also heads the country’s main Islamist party in the governing coalition, penned a letter to Hamas’s political leader Ismail Haniyeh praising the organization’s “victory” over Israel in the recent fighting. Then in June, Haniyeh himself traveled to the kingdom for an official visit, meeting with high-level figures in and out of the government and receiving a royal dinner hosted in his honor by the King.

These developments, while disturbing to the extent they lent Hamas additional legitimacy, reflected domestic Moroccan political dynamics more than a desire on the part of the monarchy to renege on its commitment to restore relations with Israel. In Morocco, foreign policy (along with military affairs and control of the religious realm) remains firmly in the purview of the Palace, and elected ministers are largely expected to carry out royal policy even if it goes against their own ideological leanings. The elected legislature, meanwhile, tends mostly to domestic economic and social affairs. The country is slated to hold parliamentary elections in September, and Othmani’s Party of Justice and Development (PJD) – a party with roots in the Muslim Brotherhood that has dominated the legislature since Morocco’s variant of an Arab Spring in 2011 – is not expected to do well. The Prime Minister’s outreach to Haniyeh was likely aimed at burnishing the party’s credentials after months of facing criticism and internal dissent over the resumption of ties with Israel. For his part, the King cannot be seen at home as ceding ground on the Palestinian question to the PJD, which likely explains the royal imprimatur on Haniyeh’s visit. The Palace also sought to demonstrate to Washington that Rabat can serve as a useful mediator between Israel and the Palestinians should that ever prove necessary – implying an additional reason for the Biden administration to maintain the Sahara recognition.

Notwithstanding Morocco’s diplomatic dance with Hamas over the past two months, the monarchy has also conveyed that the kingdom intends to continue developing its relationship with Israel. On the day Haniyeh landed in Rabat, the King warmly congratulated Prime Minister Naftali Bennett on the formation of his government. Morocco has reportedly begun planning to upgrade its liaison office in Tel Aviv to an embassy, and on July 4 a Moroccan Air Force cargo plane landed at the Hatzor Air Base, reportedly to participate in a military exercise with the IDF. Seen in this context, Ushpiz’s visit, coming on the heels of a call between Foreign Minister Yair Lapid and his Moroccan counterpart, Nasser Bourita, injects additional momentum into the renewal of bilateral ties and offers an opportunity to begin translating a promising agreement on paper into more substantive policies in practice.

Where the normalization process goes from here will depend on both sides, but Israel can take steps to build on Ushpiz’s visit and begin planting the seeds of a deeper, more sustainable bilateral relationship that can withstand external shocks such as the recent escalation in Gaza. The countries are reportedly set to launch direct flights, which will be a good start, but beyond encouraging tourism in both directions and more generally emphasizing the cultural links between the kingdom and Israeli Jews of Moroccan origin, Israel would do well to quietly but methodically focus on nurturing relations with Morocco’s business community.

Broadly speaking, the Moroccan public falls into three categories when it comes to normalization with Israel: those who fervently oppose the agreement (most vocally in Islamist and certain leftist circles), those whose sympathies with the Palestinians rendered them skeptical but were willing to give the agreement a chance, and an enthusiastic, if quieter, group eager to see relations thrive. Guardian of the Walls was most consequential for the second and third groups, insofar as skeptics of the agreement saw in the Israeli operation (and the anti-Israel propaganda surrounding it) a confirmation of their biases concerning the broader Israeli-Palestinian conflict, while normalization enthusiasts faced greater difficulty touting the benefits of closer ties to Israel. Quiet, less visible, but determined outreach to the Moroccan business community – heavily represented in both groups – would go a long way toward regaining public buy-in for the agreement.

For starters, the country is keen to gain access to Israeli technologies and investments, particularly those bearing on agriculture, which remains a dominant sector of the Moroccan economy. Likewise, a small but promising tech sector has emerged in the kingdom, where youth aged 15-24 make up a third of the country’s population of 36 million and are keen to enter the global economy. As such, Jerusalem would do well to devise plans to demonstrate to this younger demographic sector that connecting to the Israeli hi-tech ecosystem offers them one such entry point. Tax incentives for Israeli companies investing in Morocco and/or otherwise linking up with Moroccan business ventures would signal to Rabat that Jerusalem takes the prospect of business-to-business ties with the kingdom seriously. Ultimately, as with all the normalization agreements, it will take two to tango, but both Morocco and Israel have a strong incentive to demonstrate that normalizing relations invites recognizable economic benefits for their populations. Doing so would deepen the bilateral relationship and produce a positive demonstration effect for other Arab states in the region

contemplating diplomatic openings with Israel.