Publications

INSS insight No. 1985, May 25, 2025

This article reviews and analyzes trends in trade between Israel and China in 2024, set against the backdrop of the Swords of Iron war and the ongoing trade war. Three key developments stand out compared to 2023. First, imports from China rose approximately 20% in 2024, following an 18% drop from 2022 to 2023. Israel continues to import more goods from China than from any other country, and in 2024, about 15% of all goods imported to Israel came from China. Second, Israeli exports to China continued to decline. In 2024, Israeli exports fell to their lowest level since 2014, increasing the trade deficit with China above $10 billion for the first time. Third, trade with Hong Kong saw a notable surge. Since 2022, exports to Hong Kong have doubled and are now at their highest level ever. In addition, this article also compares Israel’s trade with China to its trade with its two leading trading partners, the United States and the European Union. Despite the growth in trade with China, the total trade volume with China still lags behind that with the European Union and the United States. The article concludes with an analysis of the major challenges facing trade with China amid the current era of global trade wars.

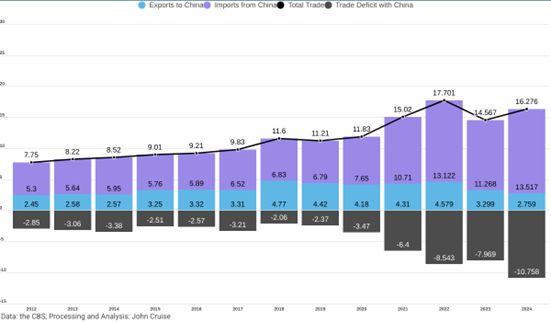

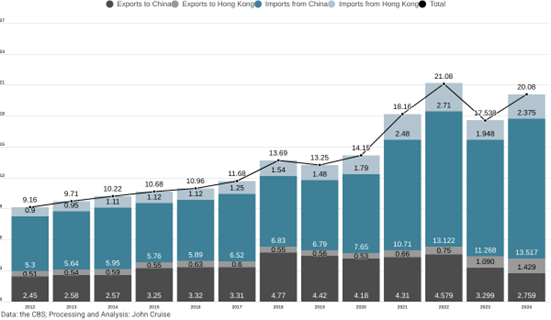

According to data from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), 2024 saw a significant increase in the volume of goods trade (excluding diamonds) between Israel and China, following a sharp decline the previous year. Trade volume reached $16.276 billion in 2024—an increase of approximately 11.7% compared to $14.567 billion in 2023 (see Figure 1). These figures represent the highest trade volumes between the two countries, with the exception of the peak year in 2022 ($17.701 billion). The primary component of trade between Israel and China has been—and remains—imports from China. In 2024, imports rose from $11.268 billion to $13.517 billion, marking a 20% increase.

Figure 1. Trade in Goods Between Israel and China, 2012–2024 (Excluding Hong Kong and Diamonds)

In 2024, the downward trend in Israeli exports to China continued, with a decline of 16.5%—from $3.299 billion in 2023 to $2.759 billion in 2024—marking the lowest volume of Israeli exports to China since 2014. During the previous decade, exports to China had risen steadily, making it Israel’s second most important export destination by 2020, after the United States (excluding the EU bloc but ahead of any individual EU member state). However, by 2023, China had fallen to third place after Ireland, and in 2024, exports to China were only slightly higher than those to the Netherlands ($2.707 billion), which ranked fourth among Israel’s export destinations.

Trends in Imports From China to Israel

Imports from China have always constituted the main component of trade relations between Israel and China. However, the combination of declining exports to China and rising imports from it has increasingly made imports more dominant in the bilateral trade relations. For many years, Israeli imports from China made up about two-thirds of the total trade volume between the two countries, while exports made up about one-third. In 2018, the peak year for Israeli exports to China, the share of imports from China dropped to 59% of total trade, while exports stood at 41% ($6.83 billion versus $4.77 billion, respectively). Despite a decline in exports in 2019, its share dropped only slightly to 40% of the total trade. However, from the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, imports from China to Israel increased while Israeli exports to China declined significantly. Trade data from 2024 reflects a peak in this trend, with the share of Israeli exports of total trade between the two countries falling to a historic low of 17%, while imports from China reached a peak of 83%—$2.579 billion in exports compared to $13.517 billion in imports. Unsurprisingly, the trade deficit with China (excluding Hong Kong) surpassed $10 billion for the first time, reaching $10.758 billion. In short, Israel’s trade deficit with China is expanding.

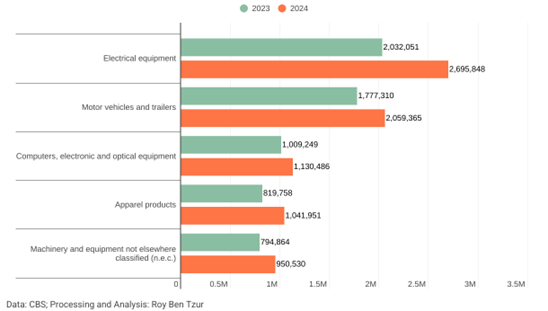

The composition of goods traded between Israel and China in 2023–2024 reflects a broad-based increase across all major import sectors. As shown in Figure 2, imports of electrical equipment grew by 25%, from $2.032 billion to $2.695 billion. The sharp rise—13.5%—in imports of Chinese vehicles also continued, from $1.77 billion to $2.032 billion. While the surge in electric vehicle imports is, of course, a global phenomenon, the trend is especially pronounced in a small market like Israel. From nearly negligible levels in 2020, imports have crossed the $2 billion mark and now constitute at least 15% of all Israeli imports from China. One in every five new cars on the road in Israel in 2024 was manufactured in China, with BYD standing out above all, accounting for a quarter of all electric vehicle sales and for the best-selling car model in Israel in 2024 (the Atto 3, both electric and gas-powered). At the same time, other import sectors also saw significant growth, including a rise of about 30% in textile and apparel products.

Figure 2. Imports From China—Key Sectors (in Millions of Dollars)

Israel’s import growth aligns with the global trend of countries increasing imports from China in 2024. Faced with limited ability to stimulate domestic private consumption in China, the Chinese government focused on expanding exports to meet its economic growth targets. As a result, China recorded an impressive 6% increase in exports globally in 2024. That year, Chinese exports amounted to $3.577 trillion, surpassing its previous record of $3.544 trillion set in 2022. To a large extent, China’s export push played a key role in addressing China’s industrial overcapacity, compensating for weak domestic demand, and supporting its GDP growth.

However, the annual increase of approximately 20% in Israeli imports from China is exceptional, even relative to the broader trend. Few countries experienced such a significant growth in imports from China in 2024 compared to 2023 as Israel did. Among the exceptions were Brazil (23%), the United Arab Emirates (19%), Vietnam, and Saudi Arabia (18%), where Chinese exports also grew at comparable rates. In Israel’s case, however, this sharp increase cannot be attributed solely to China’s export efforts; rather, it is mainly the result of internal processes within Israel over the past two years.

One key factor behind this trend is the base of comparison. Trade statistics are typically measured relative to the previous year, and in 2023, Israeli imports experienced a steeper decline than global averages—both overall and specifically from China. That year, Israel’s economy experienced uncertainty due to the upheaval around the judicial overhaul during the first three quarters, followed by a particularly weak economic performance in the final quarter of the year due to the war in Gaza and Lebanon. This combination of political instability and war reduced private consumption throughout 2023. Total imports to Israel declined by about 7%, while imports from China dropped by around 15%. Against this backdrop, the approximately 20% increase in imports from China in 2024 can be explained as a rebound—a return to the general trendline that characterized Israel prior to the disruptions of 2023. In fact, compared to 2022, it should be seen as a moderate increase of about 1.5%. A second factor contributing to the rise in Israeli imports from China is private consumption, which increased by approximately 4% in 2024 due to reduced travel abroad as a result of the war. Additionally, consumer spending grew late in the last quarter of 2024, given the anticipation of new budgetary measures that took effect in January 2025. This surge in demand led to a 12% increase in imports of consumer goods. In recent years, China has supplied a large share of Israel’s imports in this category, which includes home appliances and electric vehicles.

Trends in Exports From Israel to China

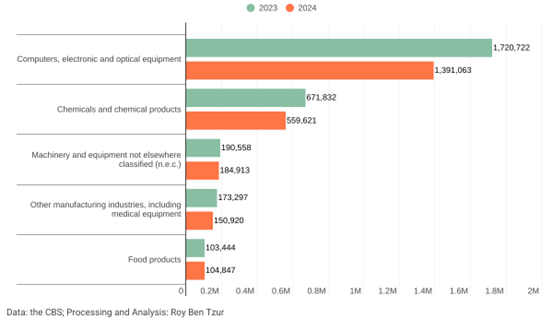

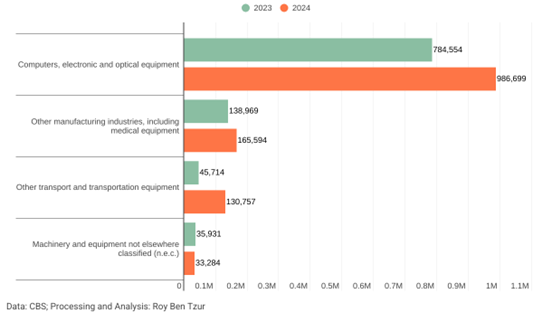

The composition of Israeli exports to China continues a trend seen in recent years: a broad-based decline centered on the computers, electronic, and optical equipment sector—the main export from Israel to China in recent years (see Figure 3). While this sector was the driving force behind the impressive growth in Israeli exports to China in the previous decade, it now leads the decline. At its peak, exports to China in this sector accounted for about $3 billion. In 2024, they fell by 23.6%—from $1.72 billion in 2023 to $1.39 billion. While the Central Bureau of Statistics’ export classifications make it difficult to identify trends within this dominant export sector, data from the UN Comtrade database provides greater clarity, revealing that the primary cause of the decline is the sharp drop in the export of semiconductors from Israel to China.

Figure 3. Israeli Exports to China—Key Sectors (in Millions of Dollars)

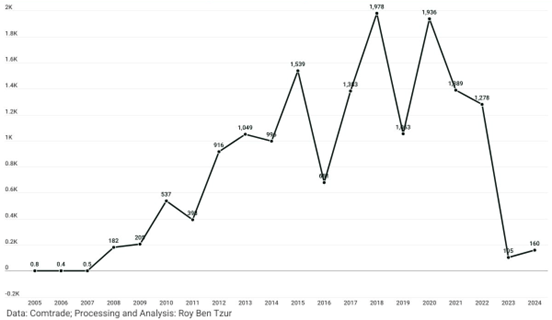

Figure 4 highlights a striking trend in Israeli chip exports to China, specifically under trade category HS 8542 (Electronic integrated circuits and microassemblies). According to this data, in the previous decade, exports in this category grew from negligible levels to approximately $1 billion in 2013, reaching $2 billion in both 2018 and 2020. Accordingly, Israeli exports to China peaked in 2018 at $4.77 billion, driven primarily by exports in this category. Between 2017 and 2022, the average annual export in this category alone was $1.5 billion. However, in 2023, this momentum reversed, with exports in this sector dropping to $105 million and to only $160 million in 2024.

Figure 4. Chip Exports (HS 8542) From Israel to China, 2005–2024 (in Millions of Dollars)

The question of what caused this collapse in exports is, of course, linked to broader developments that occurred in recent years. US President Donald Trump launched the first trade war in 2018. In 2019, Israeli exports to China in this category were halved—from $1.978 billion in 2018 to $1.053 billion in 2019. In 2020, exports recovered to $1.936 billion and remained above $1 billion in both 2021 and 2022. In other words, early indications in 2018 that the great power competition—and specifically, concerns that technological exports to China might be restricted—had not yet affected exports in category 8542. The dramatic shift began with the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, signed by President Joe Biden in August 2022. This act imposed significant restrictions on the export of advanced technologies to China, thereby directly affecting exports from companies such as Intel-Israel. The effects of the law could already be seen in 2023 and certainly in 2024. Other Western countries, including Ireland, were also affected. According to Comtrade data, in 2022, Ireland exported $8.77 billion worth of chips to China, and by 2024, that had dropped to $3.84 billion—a 56% decline.

It is noteworthy how Israeli exporters adjusted to these restrictions. Rather than suffering from the decline in exports to China, annual Israeli exports in this category underwent a fundamental shift, with volumes redirected primarily to Ireland and the United States. According to Comtrade data, total Israeli exports worldwide in category 8542 reached approximately $5.8 billion in 2024, compared to $5 billion in 2022—an increase of about 16%. In fact, despite averaging $1.5 billion annually in exports to China in this category between 2017 and 2022, companies had already anticipated the direction of US policy and began preparing for more stringent restrictions.

There is no doubt that the sector most responsible for the decline in exports to China is electronic equipment in general, and chips in particular. However, Figure 3, which presents the main export sectors, reveals a drop in nearly all categories compared to 2023, except for food products, which remained stable. For example, the export of chemicals from Israel to China markedly declined, in contrast to other countries whose exports to China increased. According to Comtrade, over the past three years, fertilizer exports from Israel to China dropped from around $400 million per year to about $200 million. During these same years, China’s fertilizer imports from Russia rose sharply—from $780 million to $1.3 billion—possibly contributing to the decline in Israeli chemical exports to China.

Trade With China, Including Hong Kong

Hong Kong is currently an integral part of the People’s Republic of China, but the World Trade Organization and other international economic organizations, as well as Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, maintain the separation between trade with China and trade with Hong Kong. Given the political reality, it is appropriate to examine trade trends between Israel and Hong Kong as part of the broader picture of trade relations with China. Trade with Hong Kong (excluding diamonds) adds $3.804 billion to trade with China. As shown in Figure 5, trade with China, including Hong Kong, reached a total of $20.08 billion in 2024. In total, trade between Israel and Hong Kong makes up less than one-fifth (19%) of all trade between Israel and China, including Hong Kong, and thus its influence on the overall trade picture is limited.

Nonetheless, trade trends with Hong Kong are interesting and present a somewhat different picture than Israel–China trade. In contrast to the continuing decline in Israeli exports to China, exports to Hong Kong continue to rise. In 2024, there was a significant 31% increase in Israeli exports to Hong Kong—from $1.090 billion in 2023 to $1.429 billion (see Figure 5). In this way, exports to Hong Kong doubled within two years and reached a record high. Israeli imports from Hong Kong also rose in the past year by 22%, from $1.948 billion in 2023 to $2.375 billion.

Figure 5. Trade in Goods Between Israel and China, 2012–2024 (Including Hong Kong, Excluding Diamonds)

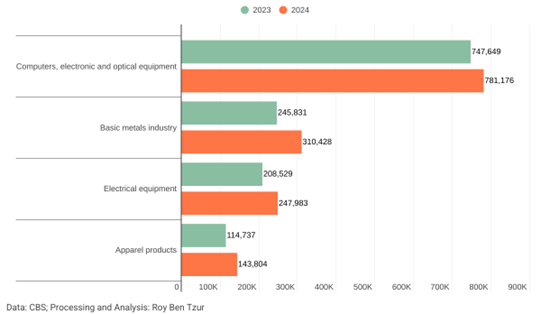

An examination of the main export and import sectors reveals an interesting phenomenon. Most notably, the bulk of the growth in exports to Hong Kong occurred in the main category of computers, electronics, and optical equipment, which jumped by $202 million—from $784 million in 2023 to $986 million in 2024—representing 60% of the total increase in exports to Hong Kong. As shown in Figure 6, there was also a significant rise—effectively a tripling—in exports in the category of other transport equipment over the past year.

Figure 6. Exports to Hong Kong—Key Sectors (in Millions of Dollars)

As shown in Figure 7, imports from Hong Kong increased across all major sectors, including a 27% rise in imports of basic metals—from $245 million in 2023 to $310 million in 2024.

Figure 7. Imports From Hong Kong—Key Sectors (in Millions of Dollars)

Trade with Hong Kong could offer valuable context to complete the analysis of Israel’s trade relationship with China, offering a possible explanation for the continued decline in exports to China, as well as an extension of shifting import patterns. First, the substantial growth in exports of computers and electronic and optical equipment to Hong Kong falls within the same economic sector in which Israeli exports to China have been in continuous decline—although not in chip exports. Second, throughout the previous decade, Israeli exports to Hong Kong remained relatively stable at around $500 million per year. From 2020 to 2024, exports to Hong Kong surged by approximately 70%, from around $530 million to $900 million. During this same period, exports to China fell by $1.4 billion. In recent years, China has tightened regulations and enforcement against foreign entities, creating increasing obstacles for exporters. In contrast, under the legacy of the “one country, two systems” principle, Hong Kong continues to offer simpler and more efficient regulatory conditions. It is possible that Israeli exporters are increasingly leveraging Hong Kong’s more favorable environment to access the Chinese market. The 15% increase in exports from Hong Kong to China in 2024 is consistent with these trends.

Impressive as it may be, the rise in exports to Hong Kong still does not fully offset the overall decline in Israeli exports. In 2024, combined exports to China and Hong Kong amounted to $4.18 billion—significantly lower than the annual average of about $5 billion per year in exports to China (including Hong Kong) during the years 2018–2022.

Trade in Goods: A Comparative Analysis

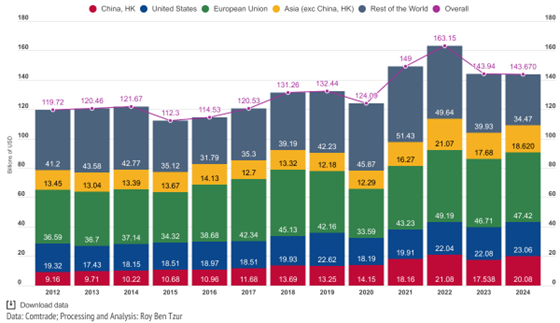

Trade in goods between Israel and China—including Hong Kong—continues to be a key component of Israel’s international trade. In 2024, Israel’s total trade in goods reached $143.670 billion, with $20.08 billion conducted with China and Hong Kong (see Figure 8). The share of trade with these two partners rose to a record high of about 14% this past year, compared to 13% in 2022.

Figure 8. Israel’s Trade in Goods with China (including Hong Kong), the United States, the European Union, Asia (Excluding China and Hong Kong), and the Rest of the World, 2012–2024 (Excluding Diamonds)

From a broader perspective, China remains Israel’s third-largest trading partner, after the European Union and the United States. In 2024, roughly one-third of Israel’s trade was with the European Union—$47.42 billion compared to $46.71 billion in 2023, an increase of only about 1.5%. The main component of Israel’s trade with the EU is imports. In 2024, imports from the EU stood at $30.7 billion compared to $29.6 billion in 2023, a 4% increase. On the export side, Israel exported goods worth $16.7 billion to the European Union in 2024, a small decline of about 1% compared to 2023.

Trade with the United States, Israel’s second-largest trading partner, grew by about 4% over the past year—from $22.08 billion in 2023 to a record $23.06 billion in 2024. The United States remains the primary destination for Israeli goods exports, with a 3.5% increase in exports to the US in 2024—from $13.7 billion in 2023 to $14.2 billion. Israel’s reliance on the US market as an export destination grew from 24% of all Israeli exports in 2023 to 26% in 2024. Imports from the United States also increased, from $8.4 billion in 2023 to $8.87 billion in 2024—a rise of 5.5%.

It should be noted that trade with China has become a significant component of Israel’s international trade in recent years. Exports to China (including Hong Kong) account for 7.6% of Israel’s total goods exports globally—$4.188 billion out of $54.89 billion. Imports are even more substantial, accounting for 17.8% of all goods imports to Israel—$15.89 billion out of $88.78 billion. However, unlike the two major trading partners—the European Union and the United States—trade with China is limited to goods. Trade in business services between Israel and the European Union, and especially with the United States, is highly significant, reaching tens of billions of dollars. In contrast, trade in services with China is marginal, amounting to only a few hundred million dollars.

Beyond the three main trading blocs, it is evident that Israel is trying to diversify its trade partnerships. Notably, Israel has increased imports not only from China and Hong Kong but also from other countries in Asia. This upward trend led to a record year in imports from Asia. In 2024, about 31% of all Israeli imports came from the East. For comparison, in 2022—previously the peak year for Israeli imports from China—imports from the East made up 27% of all Israeli imports, a level that was not surpassed until 2024.

Trade in the Era of Trade Wars

The three main trends in trade with China, as outlined above, are a significant increase in imports from China, a continued decline in exports to China, and a sharp rise in exports to Hong Kong. Together, these trends have pushed the share of trade between Israel and China (including Hong Kong) to a peak of 14% of Israel’s total international trade. In the current climate, it is difficult to predict the future direction of these trends, as they are evolving against the backdrop of unprecedented developments in global trade.

In recent months, the global trade system has entered an unprecedented period of turmoil. Trade War 2.0, which began with the return of US President Donald Trump to the White House, is once again focused on China. However, unlike the 2018 trade war, the current one is much broader in scope, threatening to erect tariff barriers across the globe that could fundamentally alter the trade system and significantly increase uncertainty. Countries are increasingly inclined to turn inward, protect local production and industries, and diversify trade partnerships to reduce exposure and dependency. A major slowdown in international trade appears to be inevitable—one that will also affect Israel. Whether it wants to or not, Israel is entering a very challenging era in the global trade system in general and within the context of the great power competition in particular.

China’s export surge over the past two years has significantly increased the volume of Chinese exports to its trade partners. Even before the start of Trump’s presidency, this trend led to rising tariffs in various countries concerned about the damage to their domestic industries. Even countries friendly to China, such as Brazil, or those heavily dependent on it, such as Russia, began raising tariffs on certain Chinese goods over the past year. This combination of higher tariffs in friendly countries and the trade war led by President Trump has prompted China to intensify its efforts to export to markets with lower tariff barriers.

This combination raises the risk of cheap Chinese goods flooding the Israeli market, potentially harming local manufacturers, as has already been seen over the past year. Data from the Manufacturers Association of Israel revealed a surprising picture: nearly 5% of all aluminum rods and profiles exported from China in 2024 were shipped to the relatively small Israeli market. In fact, over the past year, Israel was one of the five largest importers of aluminum rods from China. Local aluminum manufacturers have already protested the imports and requested an investigation into whether Chinese aluminum products are being “dumped”—i.e., sold below production cost or at prices lower than those in the exporter’s domestic market—thus causing harm to the local industry. In early May, even before the investigation concluded, the supervisor of trade levies at the Ministry of Economy imposed a temporary tariff of up to 146% on imports of aluminum rods and profiles to protect local industry. In doing so, Israel joined a long list of countries that have imposed restrictions on aluminum imports from China to safeguard local industries. Given the current climate, there is concern that additional Israeli industries may suffer as a result of China’s increased exports. Israel should closely monitor global developments, including the restrictions and justifications adopted by other countries, and adjust its policies accordingly.

Moreover, under the Trump administration, Israel is likely to face increasing pressure in international trade. This pressure has already manifested in the imposition of a 17% tariff on Israeli goods entering the United States. In response to Trump’s tariffs, Israel eliminated all tariffs on American goods exported to Israel and committed to eliminating its trade deficit with the United States. In April 2025, it was reported that American pressure led to the cancellation of Israel’s contract with China’s CRRC company, which was supposed to supply train cars and locomotives for the Jerusalem light rail’s Blue Line, scheduled to open in 2030. The US administration cited the company’s alleged ties to the Chinese military, and similar concerns could arise regarding other Chinese companies and products, potentially further straining Israel’s trade relations with China.

Conclusion

Trade between Israel and China has undergone dramatic changes in the third decade of the 21st century. The second decade was characterized by a steady increase in both imports from and exports to China, and during those years, Israel capitalized on the opportunities presented by trade with the world’s second-largest economy. Gaining a foothold in the growing Chinese market benefited Israeli exporters and enabled Israel to diversify its export destinations. Concurrently, Chinese imports helped alleviate Israel’s high cost of living. In contrast, the third decade has been marked by fluctuations driven by both domestic factors, such as the Swords of Iron war and political upheaval, and global influences like the COVID-19 crisis and the global power struggle.

The collapse of Israeli tech exports to China and Israel’s apparent withdrawal from a railway vehicles contract with China’s CRRC under US pressure highlight how trade decisions with China are not made solely in Jerusalem. Still, even within this context, it is important to define the strategic boundaries to maximize the benefits of trade relations with China. On the international level, despite the rhetoric against China—both during the Biden and Trump administrations—the United States is not disengaging from China, nor are other Western countries, such as Australia, despite its direct clash with China in 2020. Similarly, Israel is not decoupling from China and is unlikely to halt its bilateral trade. Even in an era of trade wars and increasing self-reliance, foreign trade will remain a key interest for both Israel and China. To realize this interest, Israel must conduct a trade policy with China that considers not only economic benefits but also national security, protection of local industries, and, critically, the preservation of its special relationship with the United States.

In terms of exports, the more sensitive and strategic sectors, including technology, have already felt the impact and will likely continue to be affected. Minimizing damage depends on continued dialogue with the Trump administration on technology in general and semiconductors in particular. Enhancing that dialogue will help identify red lines and areas of flexibility in other sectors as well. However, given the impressive growth of Chinese exports and the global concern it has generated, it is important not to overlook that China is also one of the world’s largest importers—purchasing around $2.5 trillion worth of goods annually, second only to the United States. Despite its push for self-reliance, China still depends on imports. Therefore, Israel should identify non-sensitive sectors where its exports to China could expand.

As for imports, Israel should closely monitor global developments regarding imports from China, particularly in relation to anti-dumping concerns in the West. Western countries are increasingly cautious about Chinese imports, such as smartphones, electric vehicles, computers, cameras, sensors, surveillance tools, and data collection tools. Israel should keep up with these developments while also conducting its own cost-benefit analyses of such imports. This should also be done in close coordination with the United States, seeking a balance between economic priorities and security and strategic considerations.

Moreover, as described in this article, the increased influx of competitively priced Chinese goods poses two primary risks. First, harm to local industries—especially when imports are unfairly priced—requires state intervention and protective measures. Second, rising dependence on China is strategically risky. Israel must diversify its import sources, as growing reliance on a single source carries significant risks in an era of trade wars, as illustrated by other disruptions such as Turkey’s boycott of Israeli goods that began in May 2024.

Trade relations between Israel and China have entered a whirlwind of geopolitical tensions and global instability, making bilateral trade far riskier than ever before—economically, strategically, and diplomatically. However, with careful policy calibration, Israel may still achieve a positive outcome under these conditions—resulting in a more balanced trade relationship that takes into account Israel’s security considerations, its relationship with the United States, local industries, and the interests of Israeli consumers. Going forward, Israel must steer its trade policy with prudence and continue to trade with Europe, the United States, and China in a way that minimizes the collateral damage from the great power competition and the current trade war.