Publications

A Special Publication in cooperation between INSS and the Institute for the Study of Intelligence Methodology at the Israel Intelligence Heritage Commemoration Center (IICC), November 12, 2024

In recent years, Iranian actors have carried out a range of hostile influence operations as part of the Israeli public discourse, aiming to expand social and political rifts, create political tension and chaos, and encourage demonstrations and distrust of the government and its democratic institutions. Since the outbreak of the war in Gaza, the Iranian influence operations have focused on issues related to the war and the attempt to sow distrust and demoralization, incite violence against Arab citizens, and deeply penetrate the discourse surrounding the issue of the return of the hostages. These operations have been conducted on a variety of social media platforms, have used artificial intelligence tools, and have simultaneously attempted to influence both the general public and individuals to advance the operations’ objectives.

The Iranian influence operations blur the boundaries between the digital realm and the physical world, as well as between influence, recruitment, activation, and intelligence-gathering practices—a combination that produces new threats in the digital realm. The State of Israel should respond to the threat of Iranian influence efforts in the digital realm. It should work toward an integrated solution that includes diverse spheres of action—legislation, developing technological solutions, advancing research and public literacy—while involving all the players in the field, such as the security forces, research bodies and academia, the media, civil society organizations, legislators, social media platforms, and tech companies.

The use of the digital dimension in war aims to undermine citizens’ ability to clarify reality and blur the lines between truth and lies, victims and perpetrators, and winners and losers. The enemy not only uses fake accounts and floods the internet with manipulative content and narratives, but it also receives assistance from local forces within Israel. The enemy promotes or supports local content while exploiting local people who echo and disseminate its content and narratives. This phenomenon represents an increased blurring of the country’s sovereign borders, the boundaries between the physical world and the digital realm, as well as those between influence operations, intelligence gathering, and recruitment. [2]

The social media platforms have, in a sense, become “mediators” in the information war, enabling hostile agents to widely disseminate harmful content and false information on their platforms. These platforms, which were once seen as promoting open communication, have now become the main arena where the digital dimension of war takes place, with the enemy exploiting them to disseminate disturbing content, incitement to violence, and false claims.[3]

This article examines the Iranian influence operations that have been carried out in Israel during the Swords of Iron war from October 2023 to May 2024. It relies on a broad analysis of social media accounts that were part of influence operations active in the Israeli discourse from 2020 to 2022, which were published in the Israeli and international media and described in depth in the article “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel.”[4]

We begin the article by describing the target audiences of the main influence operations during the first few months of the war. We then present an analysis of the phenomenon, identifying main patterns and describing significant case studies of the operations. Finally, we provide a look into the future, including an assessment and recommendations for state authorities, the companies that operate the platforms, media organizations, civil society, and the public.

Iran in the War in Gaza

To better understand Iran’s cyber operations during the war in Gaza, it is essential to first examine Tehran’s interests in the military campaign. Iran’s involvement is driven by specific strategic objectives of the Iranian regime and does not occur in isolation.

After Hamas’s invasion of southern Israel on October 7, the Iranian leadership was caught off guard by the timing of the attack.[5] In response, the Iranians made a strategic decision to push for a quick ceasefire, aiming to maintain Hamas as a significant military and political force in the Gaza Strip.[6] To this end, Iran activated its proxies—Hezbollah, the Houthis, and the Shiite militias in Iraq—to target both the Israeli army and the American presence in the region. The objective was to exert pressure on Washington to cease its support for Israel or to force Jerusalem to end the conflict. At the same time, Tehran sought to avoid a direct military confrontation with Israel, fearing it could escalate into a broader conflict with US forces in the Gulf, especially given Washington’s unprecedented show of support for Israel, including deploying aircraft carriers to the region and issuing a clear warning to Iran not to intervene in the war (“Don’t!”).

Given this policy, Iran viewed the cyber domain as the only way to directly increase friction with Israel during the war without risking a direct Israeli response. Tehran believed that through cyber, it could exact a price on Israel while avoiding attribution, given the difficulty of proving Iran’s involvement.[7] In this way, Tehran aimed to fulfill its strategic objectives without incurring significant repercussions. Moreover, the fact that Iran had been conducting large-scale influence operations against Israel for some time without escalating tensions likely bolstered its confidence in continuing and intensifying these operations. Iran believed that it could accomplish its goals using the same infrastructure, modus operandi, and especially the same tools. It appears that Iran believes that weakening Israel’s internal cohesion during the war could expedite or at least promote the understanding within Israel of the need to end the war in Gaza, aligning with Iran’s objective of avoiding a large-scale escalation.[8]

It is important to note that the cyberattacks carried out by Iran since October 7 have aimed to support these objectives. Iran has targeted “support” infrastructure critical to Israel’s military operations, such as civilian hospitals that have weak defenses. These attacks have served the cognitive aspect of Iran’s strategy and allegedly have damaged critical infrastructure, hampering Israel’s war efforts. Iran has even glorified these operations, effectively hitting two birds with one stone, as it increases the pressure on the Israeli government to stop the war. It seems that Iran believes that a combination of actions by its proxies and its own direct cyber actions “below the threshold of escalation” allows it to achieve its strategic objective of preserving Hamas in Gaza, without paying a heavy price in a direct conflict with US forces in the region.

The Findings

The Iranian influence operations focus on exploiting existing disagreements and rifts. It is not surprising that the Iranians took advantage of the war in Gaza to interfere and attempt to exert influence. They have used this opportunity to advance their strategic objectives by capitalizing on internal tensions in Israel, such as the hostage issue, the number of casualties, the lack of trust in the government and government institutions, and lack of confidence in the security forces, as well as the escalating divisions within Israeli society.

Iran’s influence operations are evident in various issues, particularly those that are controversial and receive significant public attention. The operations and the profiles they use have addressed a wide range of topics. These operations have not been limited to advancing a specific political agenda or candidate but rather have focused on whoever they believe would serve their interests most effectively. The operations described in this study were carried out using fake social media accounts, which can be attributed with a high degree of certainty to foreign state entities, specifically Iranians. The identification of these operations is based on statements by the General Security Service (Shin Bet) and their publication in the media. This study specifically examines seven foreign influence groups that were active during the first six months of the war in Gaza, from October 2023 to May 2024.

The Foreign Influence Operations in This Study

Aryeh Yehuda News Flashes

The goal of this operation was to spread propaganda and false information while posing as a local news updates channel. The operators opened groups on various platforms, including WhatsApp, Telegram, and Facebook, presenting themselves as an extreme right-wing Israeli group. Through these accounts, they disseminated incitement against Arab Israeli citizens, imitating a local extremist right-wing channel. They also targeted the security forces and various public figures, seeking to sow chaos and division in Israeli society. In addition, they attempted to encourage violent gatherings outside hospitals, spreading disinformation about “terrorists” being hospitalized throughout Israel, as discussed below.

Egrof (Fist)

This operation presented itself as an extremely right-wing Kahanist group, using TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp. This group disseminated extreme content, with the aim of sowing divisions and tensions in Israeli society and increasing friction between Jews and Arabs, as well as incitement against the Israel Security Forces. Those behind this operation also attempted to contact real Israeli activists and promote a demonstration in Jerusalem, causing significant security tensions.

Dema’ot HaMilḥama (Tears of War)

This operation maintained a database of individuals who had been murdered, killed, or taken hostage. It posted stylized content with photographs and promoted content to inflame tensions and encourage radicalization. This group also engaged in deceptive recruitment tactics, specifically targeting Israelis and enlisting their help in performing tasks related to the hostage issue, such as putting up signs in public and assisting with local procurement. It even went as far as to publicize “job offers” on various job search websites and groups.

BringHomeNow

This operation utilized Telegram and embedded itself into legitimate, authentic online activity, using names and hashtags that were similar to those used by the Hostages Families Forum.[9] Its main goal was to establish a local presence and collect personal information from Israelis by directing individuals to a “volunteer” form where they were asked to fill out their personal info. As part of their efforts, signs bearing this operation’s name were put up on bus stops in Tel Aviv, and it even ordered a wreath for the family of one of the hostages.

Ḥasrot onim (Helpless)

This operation sought to embed itself in the local discourse while disseminating messages that aimed to demoralize Israeli women, including female soldiers, women who had been injured or killed, and female hostages, by portraying them as “helpless.”

Kan+

Digital assets were used to promote a fake platform for conducting research and surveys, leveraging visual elements associated with the Kan 11 TV channel. The apparent objective of this operation was to gather information about Israelis who contacted them and responded to their surveys.

Second Israel

For more than two years, this operation focused on various issues in the Israeli public discourse.[10] In 2021, it simultaneously operated multiple social media accounts that opposed religious influence, supported the separation of religion and state, and championed the rights of the LGBTQ+ community. However, this operation also maintained accounts that impersonated well-known rabbis and incited against secular people, women, and the LGBTQ+ community. During the elections for the 25th Knesset in 2022, this group worked to influence left-wing supporters, disseminating messages against Itamar Ben-Gvir by portraying him as “dangerous for Israel,” while at the same time promoting a campaign about “election fraud” led by supporters of the Likud Party and the right wing. Following the outbreak of the war in Gaza on October 7, this operation shifted its focus and began responding to the ongoing events. It promoted a “treason from within” conspiracy theory and incited against the protestors who opposed the “regime coup.” At the same time, it also blamed Netanyahu for the October 7 events while disseminating videos of Netanyahu created using deepfake technologies.[11] The same operation promoted a deepfake video depicting several well-known rabbis blaming Netanyahu for the debacle that led to the October 7 events.

The Diverse Target Audiences of Iran’s Influence Operations—Playing On Every Team

The attempt to simultaneously target all sides using influence operations has already been described in a previous study.[12] An example of this can be demonstrated in two graphic images that were published by the same operation, targeting both supporters and opponents of Netanyahu and Bennett (see Figure 1). Another example can be found in the “Second Israel” operation, which lasted for two years and was exposed in Haaretz newspaper about two months after the war began. [13] Even before the outbreak of the war, this operation had been discussing various current events in the Israeli discourse, and in 2021, and again following October 7, it began to operate different accounts sharing opposing messages, as discussed above.

The Iranian influence operations target different audiences simultaneously in the digital realm. In the current context, there are several main themes directed at the different target audiences on both ends of the political discourse:

- Expanding military force, continuing the war, and even resettling the Gaza Strip;

- Returning the hostages as part of a deal and ending the war;

- Protesting against the judicial coup and appealing to opponents of Netanyahu

- Supporters of Netanyahu and the government.

Figure 1. Simultaneous Campaign Directed at Different Target Audiences by an Iranian Influence Operation

Note: On the left, “Netanyahu… is the real COVID in Israel.” On the right, “Bennett . . . is the real COVID in Israel.” From Orpaz and Siman-Tov, “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel.”

Several groups, such as “Fist” and “Aryeh Yehuda News Flashes,” promoted and echoed calls to continue the war and intensify the use of force, with some advocating for the conquest of the Gaza Strip and the establishment of settlements in Gush Katif. In contrast, a few groups such as “BringHomeNow,” “Tears of War,” “Helpless,” and the “Second Israel,” called for prioritizing the return of the hostages through negotiation and a ceasefire.

These groups targeted distinct audiences even before the war broke out, aiming to exacerbate and widen social divisions. Some groups promoted statements against the government, calling for Benjamin Netanyahu’s removal, while others disseminated inflammatory messages, blaming the opponents of the “judicial reform” and the “Kaplan protestors” for the October 7 events. In addition, these groups sought to incite real-world violence against Israel’s Arab citizens.

A Shared Modus Operandi of the Operations

The influence operations followed a similar modus operandi to those described in previous studies.[14]

Digital Assets Across Multiple Platforms

The Iranian influence operations extensively utilized major social media platforms, including X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, WhatsApp, and Telegram. An analysis of these operations within the context of this study reveals a focus on the “quality” of the digital assets (accounts, channels, and so forth) rather than their “quantity.” Although the number of operations spanned different social media platforms, the number of active profiles was relatively limited but of high quality. That is, the Iranian operations chose to invest resources in managing a smaller number of high-quality digital assets rather than a large volume of lower-quality ones.

Branding and Organizing Around a Central Fictitious Body or Organization

The Iranian influence operations were clearly organized around a central “brand” while building and investing in digital assets across various social media platforms. The choice of operation names and images, logo design, and consistent design themes for graphic publications demonstrated a deep understanding of the local Israeli discourse and nuances. The advanced preparation of these digital assets gave them a professional image and enhanced their credibility. By investing in the development of a comprehensive and consistent “brand,” the influence operations were able to establish clear identities that could be adapted to the different target audiences.

A Support Network of Fake Profiles

To support the branded digital assets of the various operations and enhance their credibility, a limited number of high-quality fake accounts, posing as belonging to Israelis, were used. These accounts specifically served as “contact people” for communication about the campaigns and messages promoted by the operation. In addition, a large number of lower-quality fake accounts (bots) were sometimes used with less effort. These accounts played a role in increasing visibility by reposting materials, hashtags, and messages across the various social media platforms. These accounts also artificially promoted the main digital assets through likes, shares, comments, and direct referrals.

Expanding the Activity to Additional Internet Services Compared to Previous Operations

In addition to utilizing social media platforms, there has also been a growing trend of using other free and open internet services for information gathering, such as Google Forms, petition websites like Drove, landing pages that consolidate the various digital assets, and PayPal accounts for fundraising.

Use of AI Tools

One notable application of AI tools during the war in Gaza has been to design and disseminate placards and deepfake videos. While these AI products are not yet at a perfect level of production, their quality is relatively high, and they can easily deceive citizens, the media, and elected officials. Moreover, the quality of these AI products, as well as the extent of their distribution, is rapidly increasing. As a result, they present a significant challenge in identifying, monitoring, verifying, and countering false information.

“The Second Israel” disseminated two deepfake videos as part of its operation. In the first video, Prime Minister Netanyahu supposedly speaks to world Jewry and explains in English why he is not responsible for the October 7 massacre (See Figure 2). He names who is really to blame in his opinion, including the IDF, the security forces, the police, the opposition, and the demonstrators against the government, and calls on viewers to invest in Israel in order to prevent economic damage to the country.[15] In the second video, five senior Israeli rabbis supposedly accuse Netanyahu of strengthening Hamas, dividing the nation, and for causing the debacle that led to the October 7 events (see Figure 3). They call to stop the war and return the hostages.[16]

Figure 2. Deepfake Video of Prime Minister Netanyahu from a YouTube Account Posing as Netanyahu’s Account

Note: The caption reads “Netanyahu’s important message to Jews worldwide about the fighting in Gaza.”

Figure 3. Deepfake Video of Rabbis against Netanyahu

Note: Across the top, it reads “Rabbis rebel against Netanyahu,” and in red, “Warning: Fake.” The red does not appear in the original video and was added when publishing the film in Haaretz.

Blurring the Boundaries between the Digital and Physical Worlds

Using the Physical World to Increase Credibility in the Digital World; Using the Digital World to Create Real Events

Influence operations aim to shape the local discourse in order to achieve their strategic objectives. As mentioned in the introduction, Iran, despite being physically distant, has both the capability and motivation to operate in the digital realm with the intention of manipulatively influencing the general public, opinion leaders, journalists, and decision-makers. Iranian influence operations go beyond the boundaries of the digital world and attempt to create sensational fabricated events or dramas that capture local attention and shape the discourse. In addition to these efforts, these operations are increasingly extending their influence from the digital realm to the physical world.

Familiarity With Local Discourse, Radicalization Attempts, and Creating Violence—“Aryeh Yehuda News Flashes” as a Case Study

These influence operations are not detached from the local Israeli discourse. Instead, they exploit existing divisions or key issues in the local discourse. For example, the extreme right-wing Hebrew-language Telegram channel “Nazi Hunters” shared photographs of well-known Palestinians with crosshairs over their faces and details about them, intended to incite viewers. Shortly thereafter, the “Aryeh Yehuda News Flashes” Telegram channel posted similar photographs and details of Arab Israeli citizens with crosshairs on their faces. This demonstrates a keen awareness of and familiarity with the local discourse, as well as an intent to radicalize the local discourse and incite violence in the real world.

In a calculated effort to provoke physical violence in the days following October 7, the “Aryeh Yehuda News Flashes” Telegram channel posted false information, claiming that “Palestinian terrorists” were hospitalized at various hospitals across Israel, with the intent of causing citizens to protest and engage in violence at multiple hospitals in Israel. On October 11, 2023, members of La Familia, a far-right extremist group of fans of the Jerusalem Beitar soccer team, went to Sheba Hospital after hearing reports that a “Palestinian terrorist” was being treated there. They attempted to break into one of the wards and caused a disturbance at the entrance to the emergency department, resulting in the arrest of three of them.[17]

Creating Media Storms and Taking Control of the Local Discourse

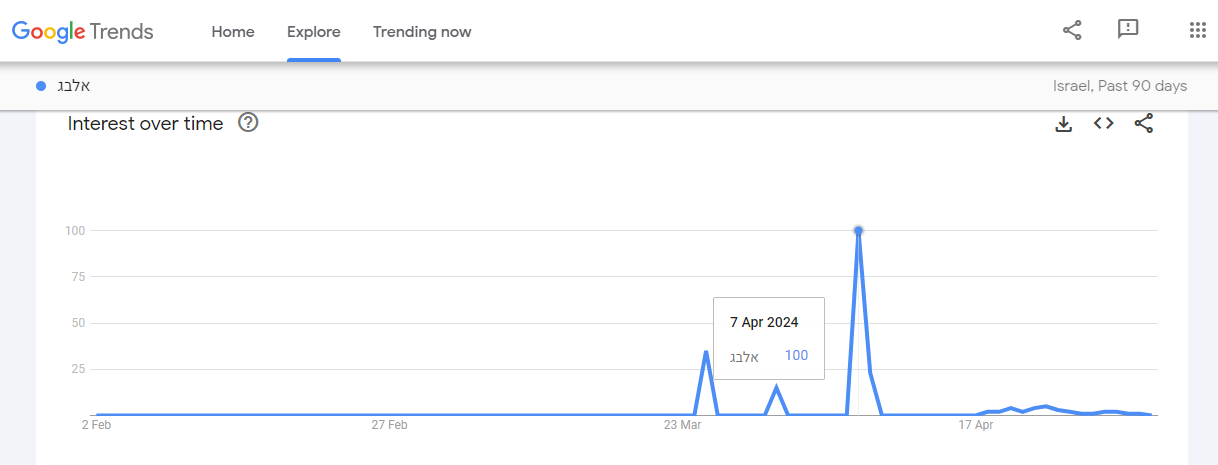

The act of sending a funeral wreath to the home of the parents of Israeli hostage Liri Elbag on April 7, 2024, was an unusual incident that revealed the unique use of digital assets by Iranian operators to create a media storm. Accompanying the wreath was a card that read “May her memory be blessed. We all know that the country is the most important.” The wreath and message immediately raised suspicions since Liri Elbag was still alive and had not been declared dead.

Nonetheless, this action demonstrated the operators’ close familiarity with the hostage situation and the families involved. It is likely that the intent behind sending the wreath and the card was not only to cause sorrow for Elbag’s parents but also to generate media attention and publicize the painful incident. Indeed, it did not take long for the public and media uproar to ensue. Liri Elbag’s mother was interviewed on Keren Neubach’s radio program “Daily Agenda” and asked, while crying, “Who does something like that? Is it my fault that my daughter is a hostage? Do I need to apologize for fighting to bring her back?”[18] Before it was apparent that Iranian operators had purchased and delivered this wreath,[19] different groups in Israeli society accused the other sides of sending the wreath.

The incident also demonstrated the ability of the influence operations to create spins, take over the public and media agenda, and fuel hate, anger, and distrust between different segments of Israeli society and between the Israeli public and the state’s institutions. The effect of this incident can be observed on Google Trends, which shows a surge in interest in the name “Elbag” on the day this incident was made public (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The interest in “Elbag” following the sending of the wreath

Source: Google Trends

Furthermore, this incident can be viewed as a demonstration of the operators’ deep understanding that a simple message like this would create a media storm when received by the hostage’s family. It took place against the backdrop of the debate in Israel about the return of hostages, which created a divide between those advocating for achieving a “total victory,” seen as “for the good of the country,” and those favoring the return of the hostages, seen as “harming the war effort.” The seemingly innocent wording of the note perfectly aligned with the deep and painful rift in Israeli society and cynically exploited the anguish and worry of the hostage’s parents.

The deep familiarity and understanding of the domestic arena in Israel, as well as the audacity of the operators, are further demonstrated by the way in which the wreath was ordered. It was discovered that Iranians, using an Israeli mobile phone number and whose WhatsApp account was connected to the fictitious BringHomeNow operation, had contacted a local Israeli flower store and ordered the wreath. The email address provided was under the name of a policeman who had been murdered on October 7 and whose body was being held in Gaza. The order was placed under the name Berezovsky, which is the surname of the Shin Bet director.[20] Moreover, it was revealed that the name of the person who had paid for the wreath had also purchased advertisements[21] on the popular Telegram channel of Israeli blogger Daniel Amram, who had promoted and recommended the Telegram channel “Tears of War,” a digital asset that was used in an Iranian influence operation.[22]

The details of this incident also highlight the importance of constant tracking, archiving, and organization of existing information in helping to identify other events, accounts, or content as part of foreign influence operations. The Shin Bet’s statement and report disclosing a forensic connection to an Iranian influence operation were quickly published in the media, thus preventing further dissemination and development of the discourse surrounding the incident.

Creating a False Impression of Credibility, Authenticity, and Localness—Putting Up Signs in the Public Sphere as a Case Study

A prominent trend in several Iranian foreign influence operations, both before and after the war’s outbreak, involves placing physical content related to the influence operation in public spaces. This includes signs on balconies, placards on the street, and posters at bus stops. In Israel, these signs, placards, and posters are reportedly photographed by those who put them up and then sent to the agents of the influence operation. The images are then disseminated through the operation’s accounts on social media platforms. Evidence suggests that locals are deceived into collaborating with foreign agents via personal messages on social media platforms and instant messaging apps, being asked to place the signs, photograph them, and send the images to the operators.

This tactic—of placing signs in the public sphere, photographing them, and then posting them online—creates a false impression of credibility, authenticity, and local presence. When social media users encounter a new organization or a suspicious account, the visibility of signs in the public sphere makes them less likely to suspect that the account is foreign, malicious, or inauthentic.

The Digital Realm as an Overlapping Arena: Influence, Intelligence Gathering, and Recruitment

A distinguishing feature of Iranian foreign information manipulation and interference compared to disinformation and influence operations from other sources, is the blurring of familiar boundaries of an “influence operation” in social media platforms. For foreign state agents, the digital realm becomes an expansive arena for executing strategic objectives across various domains.

Iranian influence operations build digital assets and entities with accounts and profiles across multiple platforms, posting content aimed at shaping Israeli society and discourse. By spreading messages, graphic materials, and other content, they create a false impression of widespread political support or opposition. However, their activities extend far beyond mere influence. These digital assets are also used to contact Israeli citizens directly through private messaging apps (such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and social media platforms messengers ). This private communication further blurs the lines between influence, operations, recruitment, cyber activities, and intelligence gathering—all occurring within the same digital ecosystem, often using the same assets.

By crafting the appearance of significant and credible digital assets and spreading messages designed for influence, these operations cultivate a sense of authenticity and local following. When these assets are used to privately contact citizens, they present an even more credible image, increasing the likelihood of successful engagement.

An analysis of these influence networks during the war, as highlighted by the Shin Bet’s statement in January 2024, reveals that Iranian operations attempt to deceptively recruit Israelis for tasks through methods like fictitious job offers and distributing surveys. Private communications include requests to place signs (designed by the Iranians) in public places, photograph demonstrators or the homes of security personnel, fill out surveys, and even carry out physical actions, such as transporting packages, ordering wreaths of flowers to be delivered to the home of a hostage’s parents,[23],or paying for advertisements on popular Israeli Telegram channels.[24]

The “Tears of War” influence operation, which began after the war’s outbreak, demonstrates the multifaceted and overlapping uses of the digital realm. Iranian operations leverage the same digital assets to simultaneously pursue objectives related to influence, intelligence gathering, operations, and recruitment.

Influence Is an Opportunity During War—The War Is an Opportunity for Influence

The various Iranian influence operations in Israel during the war can be divided into three groups: (1) Operations launched after the war broke out, (2) Operations active before the war that shifted focus to events related to the war, and (3) Dormant operations, previously exposed and abandoned, that were reactivated during the war.

- Operations Launched After the War Began

Many of these operations started shortly after significant events. The following operations focused exclusively on the war:

- “Tears of War”—addressing the war, the pain of bereavement, and the grief it causes.

- “BringHomeNow”—posing as the Hostage Families Forum, attempting to gain local connections and influence the discourse around the return of hostages.

- “Helpless”—addressing Israeli women, female hostages, and murdered women portrayed as “helpless” due to the war.

- Operations Active Before the War and Shifted Focus to War-Related Messages and Content

- “The Second Israel”—which dealt with social divisions, such as tensions between secular and religious communities, rabbis and LGBTQ+ groups, and the political right and left. It also promoted election fraud conspiracy theories and engaged in private communications with Israeli citizens.

- “Two Hearts”— posed as a local dating group, using romantic deception as a means to contact Israeli citizens.

- “Aryeh Yehuda”—a right-wing news flash network that primarily focused on disseminating news and current events from a right-wing perspective.

With the outbreak of the war, the focus of these operations shifted to dealing with the war, the hostage issue, and increasing tensions around questions like the hostage deal, IDF operations in Gaza, the entry of humanitarian aid, and the resettlement in Gush Katif. They promoted incitement against Arab Israeli citizens and encouraged violent activities by right-wing activists.

The “Fist” operation, which showed an affinity for extreme right-wing content (the fist corresponds with the profile picture and the design theme of the “Kahane Lives” symbol), promoted incitement against supporters of the left and left-wing organizations and incited violence against Palestinians. Some digital assets of this operation were active before October 7, but activity in these accounts increased after the war began.

Reactivated Operations

Most of these operations’ digital assets were closed by the social media platforms after media exposure. However, accounts that “survived” the closures, particularly on Telegram, resumed activity during the war after a prolonged period of inactivity. Two examples are BBMOVEMENTS and ADUK, which were active in 2020 and 2021 and were initially exposed by FakeReporter and covered in the international media.[25] This shows how significant events, such as the war in Gaza, can trigger new influence operations, modify existing ones, and revive old assets that had survived previous shutdowns and exposure by security authorities, the media, and civil society. From this, we can learn that crises present opportunities to expand influence operations, and existing ones can be leveraged to shape and influence current events in line with the strategic goals of those behind the influence operations.

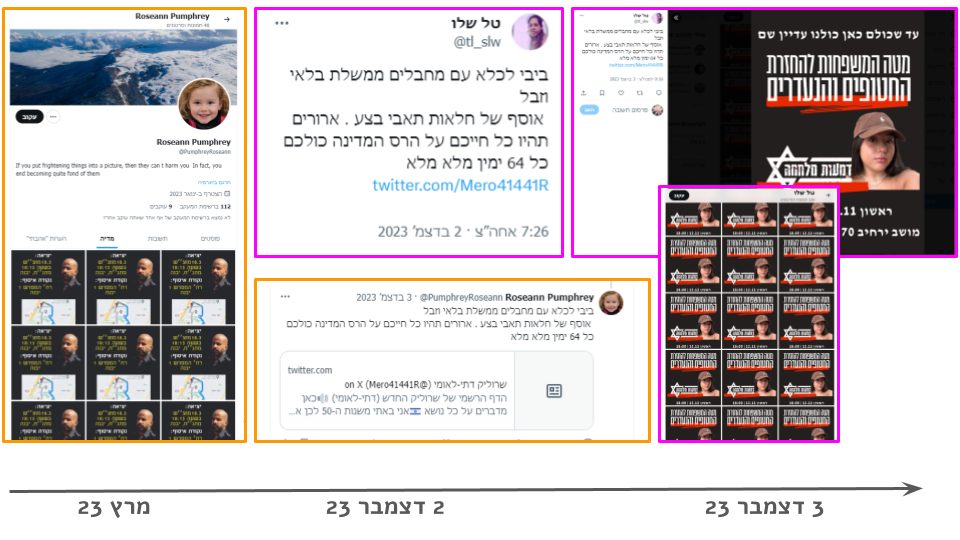

The reuse of accounts is found in both high-investment assets and simpler accounts, such as those used by bots. For example, an account that previously shared on X a post with police officers’ details during an influence operation in March 2023 later resurfaced in December 2023. This account shared a post on X (formerly Twitter) that was retweeted hundreds of times by dozens of other accounts: “Bibi to jail with terrorists, defective garbage government. Collection of greedy scum. May you be cursed for your entire lives for the destruction of the country, all of you, all 64 fully right-wing” (see Figure 5). Some of the fake accounts that spread this post in early December 2023 were also used to promote a fake event supporting the family of one of the female soldiers held hostage.

This example demonstrates how an account used on X in an influence operation in March 2023, which was not closed by the platform, resurfaced in December as part of a pool of accounts involved in a separate operation called “Tears of War” (see Figure 5). The exposure of these digital assets can create a chilling effect and, over time, can push the accounts “underground.” Often, the accounts post media articles or statements from the Shin Bet that link them to the foreign influence operations, but they typically deny the allegations, casting doubt on the credibility of these reports. The activity typically continues as long as the accounts remain active and are not shut down by the platforms.

Figure 5. Reuse of Accounts From Previous Operations

Note. From left to right, the same accounts used in March 2023, and again in December 2, 2023, and in December 3, 2023.

Conclusions

The Iranian influence efforts on social media platforms continue to use the same tactics seen in previous studies and operations before the war, while the use of diverse platforms is expected to expand further. This includes creating fake organizations and brands that exploit protest movements and civil organizations within Israel. These operations invest in high-quality uniform graphic materials and use a small number of fake profiles to directly contact citizens and local figures.

Although the overall operational methods have not changed, the operations seem to have become more precise, likely due to the experience and ongoing contact with the Israeli public, internet users, and the media. Prolonged engagement with Israeli society allows the agents of these operations to learn from public discourse, the successes and failures of previous operations, and direct interaction with citizens via private messages, further enhancing Iran’s understanding of its target audience in Israel.

Iranian influence operations and their assets are constantly evolving. The fast pace of current events in Israel provide fertile ground for new influence operations. This has been seen by the emergence of assets branded as “groups or organizations of protestors” during the demonstrations against Prime Minister Netanyahu, the protests of Likud supporters against the Bennett–Lapid government, and the protests against the judicial overhaul. These operations exploit the public’s unrest and momentum by creating shared causes and fostering interaction, and it is likely that the Iranians again will create fake civil initiatives and organizations designed to influence Israelis in response to the current events.

Exposing these digital assets should not be seen as the only means of addressing this phenomenon. The influence operations often deny media reports or Shin Bet statements about their activities, and they will continue to operate as long as the accounts remain open. In the context of Tehran’s long-term strategic objectives, exposing these operations and their digital assets serves Iran’s goals of fostering distrust in information and thereby undermining the public’s ability to make informed decisions. Additionally, this exposure strengthens the reputation of Iran’s cyber and digital capabilities and its ability to operate against Israeli society. The use of both old and new assets, which is characteristic of Iran’s influence operations, also presents an opportunity for Israel to develop defensive strategies, while learning from past operations can help identify and counter future influence operations.

An analysis of these findings shows a deep understanding of the “soft underbelly” of the Israeli public, its discourse, and the media dynamics. The influence operations are sophisticated but simple to implement, creating the “perfect storm” to advance Iran’s strategic objectives. These operations have evolved beyond merely causing a stir online—they now can create real world consequences, with local citizens unknowingly and indirectly driving the spin.

The use of AI-generated content is becoming more prevalent in these operations. Although not yet perfect, their quality is high enough to deceive citizens, members of the media, and public officials. The growing sophistication, volume, and distribution of AI-generated content create significant challenges in identifying, monitoring, verifying, and debunking it.

Looking Toward the Future

- Iran is expected to deepen its influence operations in Israel, where it has opportunities to advance its strategic objectives at a minimal operational costs and low risk of an Israeli or American response.

- The use of AI-generated content is likely to expand, improving the quality and credibility of fake content, increasing its volume and pace of distribution, and allowing more targeted messaging based on analyses of the local discourse.

- Influence operations are expected to spread to new social media platforms and internet services. The agents of the operations will exploit any platform that can effectively be used to influence the Israeli public, including those that allow direct messaging, information gathering, and the establishment of credibility, authenticity, and a local presence.

- After this study was completed, the Israeli media reported that a young Haredi man had been manipulated by an account on Telegram, supposedly belonging to a woman. According to the reports based on a Shin Bet statement, the man was asked to perform various tasks, including putting up signs, hiding packages and money, and delivering threatening messages. The man refused to carry out more serious actions, such as setting fire to a forest and harming citizens.[26] Although it is unclear whether this incident is connected to the influence operations described here, it warrants further examination, especially the targeting of the Haredi community.

Recommendations

For Policy Makers

- Israel should take Iranian influence operations seriously, both during routine times and in war. These operations pose a growing threat; by exploiting vulnerabilities within Israeli society, Iran successfully influences public discourse, generates media storms, and even affects decision-makers. Foreign influence operations should be recognized as a key threat, and appropriate resources should be allocated to address them.

- Clear distinctions should be made between the digital and physical worlds and between various operational areas within the digital realm, such as influence operations, recruitment, intelligence gathering, and cyber activities. The State of Israel needs to define which bodies are responsible for addressing these threats, while balancing the need to monitor foreign and malicious influence without infringing on legitimate internal discourse and freedom of expression.

- Plans should be developed to respond to cyber and digital attacks and hold perpetrators accountable. These activities threaten national security and erode the foundations of democratic society, and malicious actors should face consequences for their actions.

- Social media platforms should be required to address foreign influence operations transparently, providing data on their scope, target audiences, and the agents behind them.

- AI technologies enhance the scale, quality, and speed of disinformation in the influence operations. Israel should adopt technological solutions to monitor and analyze large data sets, detect behavioral anomalies, and identify fabricated content.

- Operations with a small number of high-quality assets often evade detection due to their limited scale. These operations, conducted via private messaging, present a significant challenge for monitoring and cyber defense. Israel should reassess its technological approach to identifying and countering this type of threat.

- It is important to remember that there is no “silver bullet.” A combination of technological tools and human involvement should be used to identify influence operations and neutralize them early, thereby reducing their impact.

For Research Organizations and Civil Society Organizations

- Foreign influence operations directly target civil society. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations, fact-checkers, academic researchers, and media organizations so that they can play a central role in researching, monitoring, exposing, and countering these operations.

- Efforts should be made to enhance the Israel public’s ability to critically consume information, operate safely online, and report suspicious online activities. Public campaigns and both formal and informal education are key to this effort.

- The Iranian influence operations consistently create new digital assets and reuse old ones. Israel can turn this into a defense opportunity by building a repository of knowledge to help identify and expose influence operations based on insights from past operations.

___________________

[1] Nitsan Yasur is a researcher on disinformation and social networks. Danny Citrinowicz is a research fellow in the Iran Program at INSS.

[2] This article is part of a memorandum that will be published soon on foreign influence and interference as a strategic challenge. The memorandum includes articles that examine the challenge from the perspective of adversaries (such as Russia and Iran), and discusses aspects of influence methods. It will also include an examination of the challenge during normal times and during the disruption of democratic processes, the deepening of social rifts, election campaigns, and wars. The articles reflect a connection between systemic understandings and the policy needed to address it in Israel and in Western countries. The memorandum concludes a joint project of the Institute for National Security Studies and the Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center (IICC).

[3] Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler, “The Fourth Dimension of the War is Undermining Israelis’ Ability to Clarify Reality,” [in Hebrew] Israel Democracy Institute, November 7, 2023, https://www.idi.org.il/articles/51289

[4] Inbal Orpaz and David Siman-Tov, “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel,” [in Hebrew] Special Publication, Institute for National Security Studies, June 10, 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/he/publication/iranian-influence/

[5] “Swords of Iron: The Iranian Leadership Was Surprised by the Attack on the Gaza Envelope,” [in Hebrew] Maariv, October 11, 2023, https://www.maariv.co.il/news/world/Article-1044274

[6] Ece Goksedef, “Iran Warns Israel to Stop War in Gaza or Region Will ‘Go Out of Control,’” BBC News, October 22, 2023 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67188346

[7] Chuck Freilich, “The Iranian Cyber Threat,” Memorandum No. 230, INSS, February 2024, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/iranian-cyber/

[8] “Kamal Kharazi, “Khamenei’s Advisor: Iran is Not Interested in Regional War,” [in Hebrew] Maariv, July 2, 2024, https://www.maariv.co.il/news/military/Article-1111765

[9] The mistake in the name is intentional. The idea was to be similar to the original BringThem HomeNow but not be identical.

[10] Omer Benjakob, “Fake Rabbis and AI-Bibi: For Two Years, A Foreign Network Sowed Chaos in Israel,” Haaretz, December 20, 2023, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-12-20/ty-article-magazine/.premium/fake-rabbis-and-ai-bibi-for-two-years-a-foreign-network-sowed-chaos-in-israel/0000018c-8710-de71-a3ee-e75ba3900000

[11] Refaella Goichman, “The Presenter Is Not the Prime Minister: Foreign Network Poses as Netanyahu, Using Deepfake Technologies,” [in Hebrew] TheMarker, December 13, 2023, https://www.themarker.com/captain-internet/2023-12-13/ty-article/.premium/0000018c-62ca-dbd5-a39c-fffbbda70000

[12] Orpaz and Siman-Tov, “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel.”

[13] Benjakob, “Fake Rabbis and AI-Bibi.”

[14] Orpaz and Siman-Tov, “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel.”

[15] Goichman, “The Presenter Is Not the Prime Minister.”

[16] Benjakob, “Fake Rabbis and AI-Bibi.”

[17] Liran Levi, “Clashes at Sheba: Members of La Familia Tried to Break into the Ward Where They Thought a Terrorist Was Hospitalized, 3 Arrested, Documentation,” [in Hebrew] Ynet, October 11, 2023, https://www.ynet.co.il/news/article/byjrk8vwt

[18] Karen Neubach (@kereneubach), “Shira Elbag, mother of Liri, on the memorial wreath that arrived,” [in Hebrew] X, April 7, 2024, https://x.com/kereneubach/status/1776895073944256769

[19] Yoav Zitun, Itamar Eichner, Yael Ciechanover, “Shin Bet: Iran Likely Behind Delivery of Funeral Wreath to Hamas Hostage’s Family,” Ynet, July 4, 2024, https://www.ynetnews.com/article/hkfkhzglc

[20] Yael Freidson, Yaniv Kubovich, Bar Peleg, and Omer Benjacob, “A Funeral Wreath Was Sent to the Home of the Hostage Liri Elbag; The Shin Bet assess: Iran is responsible,” [in Hebrew] Haaretz, April 7, 2024, https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/2024-04-07/ty-article/0000018e-b853-d906-a5cf-bad7f72f0000

[21] FakeReporter (@FakeReporter), “Daniel Amram published this evening the receipts . . . ” [in Hebrew] X, May 16, 2024, https://x.com/FakeReporter/status/1791194864899485978

[22] Refaella Goichman, “For 800 Shekels: The Iranians Disseminated a Campaign Against Israel on the Telegram Channel of Blogger Daniel Amram,” [in Hebrew] The Marker, May 16, 2024, https://www.themarker.com/advertising/2024-05-16/ty-article/.premium/0000018f-80c5-dd4f-ab8f-95edef020000

[23] Omer Benjakob, “Shin Bet: Iran Used Israelis to Photograph Homes of Security Personnel and Encourage Discussion of the Hostages,” [in Hebrew] Haaretz, January 15, 2024, https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/2024-01-15/ty-article/0000018d-0e82-de9c-a3df-6ffbbed60000; Freidson, Kubovich, Peleg, and Benjakob, “A Funeral Wreath Was Sent to the Home of the Hostage Liri Elbag.”

[24] FakeReporter (@FakeReporter), X (Formerly Twitter). https://x.com/FakeReporter/status/1791194864899485978; Refaella Goichman, “For 800 Shekels: The Iranians Disseminated a Campaign Against Israel on the Telegram Channel of Blogger Daniel Amram,” [in Hebrew] The Marker, May 16, 2024, https://www.themarker.com/advertising/2024-05-16/ty-article/.premium/0000018f-80c5-dd4f-ab8f-95edef020000

[25] Tom Bateman, “Iran Accused of Sowing Israeli Discontent with Fake Jewish Facebook Group,” BBC, February 3, 2022; See also Orpaz and Siman-Tov, “Foreign Interference and Iranian Influence in Social Networks in Israel.”

[26] Shlomi Heller, “Slaughtering a Sheep, Setting Fire to Vehicles, and Breaking Windows: Iranian Agents’ Demands of a Beit Shemesh Resident,” [in Hebrew] Walla, July 16, 2024, https://news.walla.co.il/item/3678174