Publications

INSS Insight No. 1306, April 22, 2020

The coronavirus crisis presents Egypt with a host of challenges, given its large, densely-packed population, an economy exposed to global shockwaves, and a fragile health system. As it continues, the crisis will likely exacerbate Egypt’s financial struggles and endanger its political stability. Those most vulnerable to the virus’ economic effects are the millions of irregular workers who have no social benefits and who are likely to slide quickly into unemployment and poverty. As such, the benchmark for the Egyptian government in dealing with the crisis is its ability to formulate a plan that balances between the need for social distancing to curb infection and the economic constraints that demand a return to routine as quickly as possible. During the pandemic, Israel can promote cooperation with Egypt on issues such as preventing the spread of the virus throughout the Gaza Strip, providing medical knowledge and equipment, and offering diplomatic assistance in the international arena.

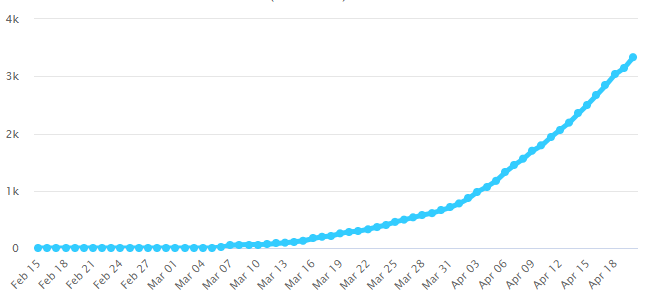

The number of Egyptians infected with the coronavirus has been on the rise since early March 2020. According to the Egyptian Ministry of Health, as of April 21 there were 3490 confirmed infected, including 264 fatalities. However, a caveat is in order, given the low rate of testing; by the end of March about 25,000 had been tested, and since then testing has continued at a rate of about 2,000 per day. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Egypt has a stockpile of about 200,000 tests, leading authorities to prioritize testing for those who have had contact with confirmed carriers and populations at risk. Egypt’s younger population works in its favor, with about 93.3 percent of the population under the age of 60.

While the international media has cited estimates that the actual extent of COVID-19 is far higher than reported, the official message from Egypt – which is supported by the WHO – is that the outbreak is under control. Yet whatever the true state of affairs may be, there are concerns regarding the Egyptian health system’s ability to cope with a large extra burden. Even in normal times, hospitals suffer from a lack of intensive care beds and ventilators, and substandard sanitary conditions make it difficult to protect medical staff and patients from the spread of the virus. Currently, Egypt has only 1.2 doctors for every 1,000 people, significantly fewer than the OECD average of 3.4 and the global average of 1.8. The shortage of sufficient medical personnel compounds the difficulty of preventing contagion in a population of 100 million people living in overcrowded conditions.

Medical Challenge, Political Opportunity

The Egyptian Ministry of Health has established a situation room to coordinate the response to the outbreak, as well as a call center to provide citizens with information. Dozens of hospitals throughout the country with over 15,000 beds have been designated for diagnosing and quarantining coronavirus patients. In addition, 1,000 ambulances have been allocated and medical sites equipped to receive thousands of cases. Meanwhile, hospital physicians have been afforded better employment terms, with their numbers boosted by medical lecturers and students. An effort is also underway to promote local manufacture of 5,000 ventilators, to add to the existing 4,000.

Since mid-March, Egypt’s strategy to reduce contagion has revolved around social distancing. Measures implemented include a nighttime curfew, shuttering entertainment centers and restaurants, a ban on smoking hookahs in public areas, the suspension of flights, quarantine of those returning from overseas, closure of schools and universities, a ban on prayers in mosques and churches, restrictions on governmental activity, promotion of working from home, reduced crowding on public transportation, bans on gatherings, and closure of sports and youth clubs. The regulations have led to a 35-50 percent decrease in traffic in public places, reflecting both the partial response by the public, and the government’s decision to refrain for the moment from harsher steps that the Egyptian economy would be unable to withstand.

For the Egyptian government, the pandemic is also an opportunity to demonstrate leadership and control, and to prove the necessity of state authorities as the responsible address during a crisis. Leading the operation is the military, which has embarked on a campaign under the name: “The Egyptian Armed Forces – the Fortress and the Support,” through which they perform a range of tasks, including: monitoring and maintaining border security, disinfecting roads and public buildings, operating military hospitals, assisting the police in maintaining public order and enforcing social distancing, preparing emergency stocks of food, and producing and supplying protective masks for free distribution to the population.

However, the challenge facing the government and the military goes beyond the faceless virus. The pandemic has already become intertwined with the public controversy raging in Egypt since June 2013 between the government and the Muslim Brotherhood: the national leadership is presented in official media outlets as the body that manages the medical and economic systems with the utmost efficiency and requisite responsibility. On the other hand, the Brotherhood is blamed and denounced as the source of rumors about increasing contagion rates in prisons, the army, and the upper echelons of the administration, in an attempt to undermine public trust in the government, encourage public disobedience of the guidelines, and ultimately push Egypt toward anarchy in an effort to return to power.

Economic Threat

The pandemic has struck at the economic progress achieved by Egypt in recent years, reflected in encouraging growth rates and lower unemployment and inflation. Specifically, the coronavirus has now weakened major pillars of the economy. Millions of Egyptians who work abroad (mostly in the Gulf states) remitted some $29 billion to Egypt in 2019, but many have been fired or had their wages cut, and may return to their home country; the tourism industry has also been particularly hard hit, having only recently recovered from the turmoil of the last decade. The sector, which saw profits of $12.4 billion, accounted for about 15 percent of the GDP, while providing some four million jobs (12.6 percent of the workforce). The aviation industry lost 2.5 billion Egyptian pounds (EGP) in March alone, and its employees asked the government for emergency aid; traffic along the Suez Canal is also expected to drop due to the recession in global trade and the plunge in global oil prices.

A major question is the potential impact the economic downturn will have on Egypt’s political stability. On the one hand, recent economic reforms have increased Egypt’s foreign currency reserves to around $45 billion and stabilized its macroeconomic position, which facilitates its current response to the crisis. On the other hand, the reforms included the elimination of subsidies and thus increased the poverty rate to 32.5 percent, and intensified the vulnerability of the middle to low socioeconomic class. According to IFPRI estimates, the crisis will cause a reduction in GDP of 0.7-0.8 percent each month, cutting average household income by about 10 percent, and increasing the rates of unemployment and poverty. In 2020, according to the International Monetary Fund, growth in Egypt will drop to 2 percent; Egypt itself revised its growth estimates to 4.2 percent (down from the expected 5.7) and reported a decrease of $8.5 billion in foreign investments.

The sector that is most vulnerable to the crisis is that of are the 12-14 million irregular day laborers, who lack permanent employment and social benefits. Most of them belong to the middle to lower class, and as their distress mounts, there will be greater potential for social unrest and protests. In order to improve their situation, the government has authorized a special grant of 500 EGP per month for three months, but it will be difficult to bear such a burden long term. Charity organizations are also gearing up to provide help for those struggling, while food chains are selling basic necessities at subsidized prices.

The Egyptian government has allocated 100 billion EGP (about $6.4 billion) to deal with the crisis, and has invested 20 billion EGP to stem the collapse of the stock exchange. Some of these moves are designed to assist businesspeople and companies in the private sector, and include reduction of interest rates and elimination of bank commissions, relief on taxation and debt repayments, a reduction in the price of electricity and gas for industry, and support for hotels. Part of the budget will be funded by postponing the launch of national projects, including the move of government offices to the new administrative capital. In addition, government ministers and members of parliament are being asked to donate part of their salary to the national fund, “Tahya Misr.”

Significance and Potential Action Items

In Egypt, even more so than in affluent Western nations, economic considerations play a vital role in any plans for a return to routine. The choice is between difficult alternatives: business people are calling for a renewal of economic activity even at the cost of higher morbidity rates in order to avert economic collapse in the form of bankruptcies, mass hunger, and anarchy; others warn that containing the spread of the virus mandates additional economic victims, such as non-essential businesses, further personnel cuts in government ministries, and perhaps even a complete lockdown for a limited period. At present, although there is no sign that the infection curve is flattening, the government is currently prioritizing partial economic activity under controlled conditions, particularly in domains such as transportation, housing, and agriculture.

At the diplomatic level, the coronavirus highlights the range of Cairo’s international ties. Egypt has airlifted aid to Italy, Britain, and the United States, and itself received aid from China, including four tons of medical equipment containing 10,000 test kits. While the United States battles soaring mortality rates, China is exploiting its status as the first country allegedly to emerge from the crisis in order to reinforce its status as a global power and increase its influence elsewhere, including Egypt. On the other hand, the crisis could cast a shadow over Egypt’s relations with its allies in the Gulf, who in view of the fall in oil prices will likely have difficulty in continuing to provide the aid and investments to which Egypt has become accustomed, or to pay wages to Egyptian migrant workers.

Israel and Egypt could promote cooperation along a range of channels: they share an interest in avoiding a medical-humanitarian crisis in the Gaza Strip, which would spill over into their borders. They could also examine opportunities to strengthen the Palestinian Authority at the expense of Hamas, for instance by positioning the PA as the coordinator of international aid to the Strip. Moreover, Egyptian mediation between Israel and Hamas is crucial at this time to prevent military escalation and in order to examine the possibility of a prisoner exchange. Israel, for its part, can help Egypt with medical knowledge and surplus equipment, and if necessary, support its requests for aid from the international community.