Publications

Special Publication, January 2, 2024

Most developed countries recognize that to meet the targets that were defined in the 2015 Paris Agreement for tackling the climate crisis, political and economic tools are necessary to facilitate the flow of money from the government and the private sector. Environmental regulations, such as carbon taxes, encourage energy efficiency and limit the use of polluting fuels, and also bring in money that promotes green initiatives and transitions to green energy. However, in Israel there is no move in this direction; there is no climate policy anchored in legislation that motivates establishment of a system of registration and trading in emissions. The carbon tax was not approved in the original budget law or in the amendment that was recently approved, and there is no incentive for the private sector to attract investment in this area. Israel thus loses twice: there is no domestic policy designed to yield funds to promote environmental goals and energy resilience, while Israeli exporters are obliged to pay carbon tax to their main trading partners – Europe, and soon the United States as well. Therefore, even and perhaps especially in the current war situation, Israel must adopt a mechanism similar to the collection of carbon tax, establish a system for trading in emissions, and direct funds toward the decarbonization of industry, such that is underway in most OECD countries, in order not to be left behind and to avoid economic losses.

One of the central issues discussed at the 28th Climate Change Conference held recently in Dubai (COP28) was climate finance, which is an essential tool for realizing the global objectives of the 2015 Paris Agreement to tackle the climate crisis in the areas of mitigation (reducing greenhouse emissions) and adaptation (adjusting to climate changes). Most countries of the developed world recognize that meeting these targets requires a large budget, and they therefore use political and economic tools to facilitate the flow of money from the government and the private sector. For example, environmental regulations such as carbon taxes encourage energy efficiency and reduction in the use of polluting fuels, and also bring in money that promotes green initiatives and the transition to green energy.

At COP28 there were discussions about setting a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance in 2024, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries. After achieving the target of $100 billion, the new target, which will start from the base of $100 billion per year, will be a building block for planning and implementing national climate programs that must be passed by 2025. The achievement recorded in the first two days of COP28 was a declaration by many developed countries of their contribution to the Climate Fund and the Loss and Damage Fund, which was set up to provide financial support for developing countries suffering from severe effects of climate change, on the basis of one of the most important decisions from the previous climate conference – COP27, held in 2022 in Sharm el-Sheikh. These contributions were intended to serve as financial resources for developing countries, as well as for knowledge and technology transfers, to help them reduce emissions, adjust to climate changes, and tackle the losses and damage that are likely to result. Therefore, climate financing is a leading priority for many countries in the negotiations over the respective economic promises. At least 15 countries and the European Union undertook to support the fund with over $650 million. Germany and the United Arab Emirates, the host country of the conference, were quick to pledge $100 million each, while France and Italy committed to the highest amount – almost $110 million each. Contributions to the fund are not mandatory, although developing countries are also expected to contribute. Among the countries that chose not to contribute are India, China, and Israel.

Climate finance is an issue not only at annual global climate conferences, but also in policy and economic tools that enable governments to direct capital toward green energy and reinforcement of national climate resilience. For example, the carbon tax mechanism is strongly recommended by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) due to its effectiveness in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and meeting global warming reduction targets, to which the countries committed as part of the Paris Agreement. According to the organization, a successful move to net zero emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) demands initiatives in the framework of effective reduction policies, including a mechanism of carbon taxation – an economic policy tool that not only reduces emissions but also creates income for other climate purposes. Another mechanism led by the European Union and particularly widespread among OECD countries is the Emissions Trading System (ETS), which allocates pre-defined emissions quotas to a company or a country. Any company or country that does not utilize the allocated quota can sell the balance to a company or country that exceeds its quota. This mechanism means that polluters must pay for their GHG emissions, and therefore it helps to reduce emissions and create income to fund the green transition of the European Union.

The 2021 Climate Conference in Glasgow saw agreement on the operation of a global emissions trading mechanism under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. During the conference in Dubai, the parties discussed Article 6 (6.2/6.4/6.8), which defines the rules for global trade in GHG emissions and is a key component for countries and businesses to comply with their climate targets and even accelerate them. While Article 6.2 provides a framework for countries to cooperate, Article 6.4 provides a centralized mechanism managed by the UN. At the start of COP28 there was considerable optimism regarding Article 6.4; its implementation would supply a new structure for the global carbon market and reduce new demand for credits, under supervision of the eligibility rules by the UN. While the lack of consensus between countries around the agreements remained disappointing, many countries will continue to implement Article 6.2, after agreement on the main guidelines drawn up at the COP26 summit in Glasgow. “Countries can and should implement international carbon markets under Article 6.2. While the lack of consensus at COP28 is disappointing, we are excited by the numerous agreements signed and projects underway," said Dirk Forrister, president and CEO at IETA (International Emissions Trading Association).

On December 7, 2023, US Congressmen Brian Fitzpatrick and Salud Carbajal presented the Market Choice Act, which replaces the federal tax on fuel with a broader tax on CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels and from large industrial sources. The bill also includes an amendment to the border tax to deal with imports and exports, and joins bills proposed by both Republicans and Democrats dealing with trade and climate. The bill will devote most of the income generated to investment in infrastructures and renew the Trust Fund for High Speed Roads currently funded by the federal gas tax. Other funds will be transferred for resilience, with the emphasis on floats, assistance for uprooted energy workers, low income households, and research, development, and deployment to remove, capture, and store carbon and advanced energy. In his announcement, Dr. Daniel Lashof, the director of the World Resources Institute (WRI), United States, said: “With 2023 almost certain to be the hottest year on record, and report after report telling us that we are not on target to meet our global emission reductions goals necessary to prevent the worst impacts of unmitigated climate change, WRI is pleased to see Representative Fitzpatrick’s introduction of the bipartisan Market Choice Act to address climate change...We are particularly pleased to see a serious bipartisan proposal to use market forces to help address climate change. We hope that additional members of both parties will support smart climate policies like the Market Choice Act, and we commend Mr. Fitzpatrick and Mr. Carbajal for their leadership.”

Similarly, on October 1, 2023, the transitional stage of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) came into force in the European Union. The new carbon tax will apply to anyone who exports energy-rich products to the European bloc, including Israeli exporters. The law will apply initially to the import of carbon rich products, such as cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen, where there is a risk of moving production to other countries that do not impose a price on carbon. The purpose of the mechanism is to reduce carbon emissions while retaining the competitiveness of the EU, so that the carbon fee imposed on some imports will be equivalent to the internal regulatory price collected by the European Union from domestic companies. In the long term, the third largest trading bloc in the world is utilizing its power to incentivize other countries to charge their manufacturers a carbon price.

Britain is not far behind, and it has decided to impose a carbon border tax that will come into force in 2027. The border tax will at first be imposed on imports of iron, steel, aluminum, ceramics, and cement, and will be similar to the carbon price for products made in Britain. Goods imported to Britain from countries with a lower carbon tax or no carbon tax will have to pay the levy by 2027, meaning that products from overseas will compete with a similar carbon price for goods made in Britain.

What is Happening in Israel?

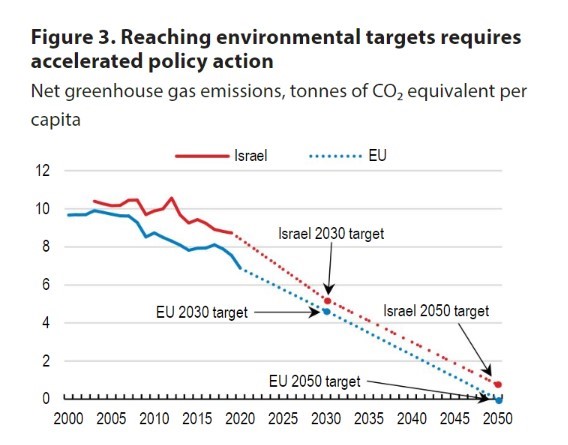

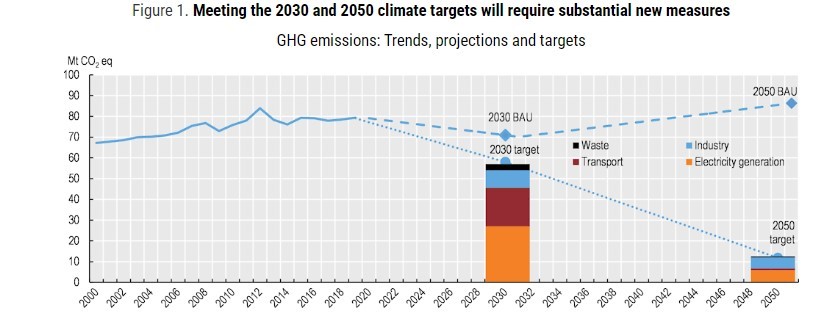

A number of OECD reports have indicated the need for progress in the use of economic tools to advance climate policy. The recommendations of the latest economic report on Israel, issued in April 2023, states that although the carbon footprint of the Israeli economy has fallen, compliance with the new and ambitious national climate targets requires additional policy actions (Figure 1).

The report explains that the discovery of large gas fields means that Israel’s total GHG emissions have stabilized in recent years, in spite of economic growth and population growth. However, emissions from transportation, industrial processes, and waste have continued to rise. The national action plan on climate change for the years 2022-2026 defines more than a hundred ways of reducing emissions from electricity, transportation, industry, buildings, and waste, but there is no discernible implementation or budgeting for most of them. Moreover, legislation could reinforce the government’s responsibility for the subject, but the proposed law has not yet been approved by the Knesset, thereby weakening its obligation. In Israel there is no explicit carbon tax, but the OECD has individually advised Israel to price carbon by means of the excise tax on fuel. Nevertheless, the increase in the excise tax will not be sufficient to reduce emissions and achieve the government’s environmental targets, and therefore the cost of emissions must be adjusted to the environmental costs. In the medium term, the authorities must aim to introduce measures for dealing with carbon emissions that are not linked to burning fuel, such as industrial processes and waste, which have risen and account for 20 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions. This can be done by enlarging the framework of carbon pricing to these sectors, or by means of regulatory steps.

The recommendations of the March 2023 OECD report on Israel’s environmental performance indicate that Israel has raised its climate goals in recent years. In 2021 Israel updated its national target for reducing GHG emissions by 2030, from the target based on reductions per head to an absolute target of a 27 percent reduction compared to 2015. A target of 85 percent reduction in GHG reduction by 2050 was also defined, as well as emissions targets for various sectors for electricity generation, solid waste, transportation, and industry, before the declaration of the aim for carbon neutrality by that year.

However, according to the OECD, Israel is not on track to achieve these targets with existing means (Figure 2) and it will have to show additional measures in all sectors. The country’s share of renewable energy in its energy mix is the second smallest in the OECD. The climate bill approved by the government in May 2022 is an important step in this direction, but the environmental regulatory framework is fragmentary and partially outdated, and Israel must make progress in removing administrative barriers. The lack of political stability in recent years hinders the efforts to upgrade legislation, creating regulatory uncertainty for businesses. The adoption of good working methods to implement environmental law is slow, mainly due to lack of resources.

Furthermore, and pursuant to the outcomes of COP28, it appears that Israel is making no preparations to implement Article 6.2, which means participation in the global market for trade in GHG emissions, as used by many countries. Contrary to the OECD recommendation to expand carbon pricing in Israel, the carbon tax was not approved. Apart from the loss of local taxes because of the European border tax legislation, Israeli companies that export to countries with an emissions trading regime, such as European countries, will have to pay tax on entering those countries. With the approval the United States bill that includes border tax, Israel companies will apparently also have to pay the border tax.

According to an analysis by the Overseas Trading Administration in the Ministry of the Economy and Industry, in 2022 some 37.4 percent of Israel’s exports were directed to US markets, about 36.8 percent to markets in Europe, and about 23.6 percent to Asian markets. A tax that could be collected in Israel and provide support for the Israeli transition to a net zero economy will be paid in tax to other countries and thus Israel is losing twice.

True, Israel is currently at war, and there is little attention to the various aspects of the climate crisis. However, global engagement with the crisis has reached a peak. Although the conference in Dubai did not pass all the ambitious resolutions that the developed world expected, Israel is in any case far from adopting and implementing regulation similar to OECD countries. The climate crisis is no less serious than wars. Countries and leading global trading blocs are adopting regulatory environmental elements, but as long as there is no regulatory mechanism for costing carbon emissions in Israel, which requires companies to make local payments and will credit them for payments to the European Union or the United States, Israel will continue to lose money in two ways: first by paying taxes on exports to Europe and the United States, and second, through the loss of cash flow that could help the local economy to implement energy efficiency measures, the transition to renewable energy, and assimilation of innovative technologies for a zero carbon economy. Israel must adopt a similar mechanism for collecting carbon tax and direct the money toward the decarbonization of industry, as is underway in most OECD countries.

Climate finance is currently increasing worldwide, while Israel lags behind. The climate issue is above all economic: countries do everything they can to maintain the competitiveness of their industry and will therefore not permit the import of raw materials and goods from countries with less strict climate policies that fail to cost carbon emissions and can therefore offer better prices than local industries. As climate policies become stricter, there are also border taxes to preserve the competitiveness of local industries while pushing others to adopt climate policy that uses economic tools. Can Israel, in a state of war and with its current economic situation, allow potential income to slip away?